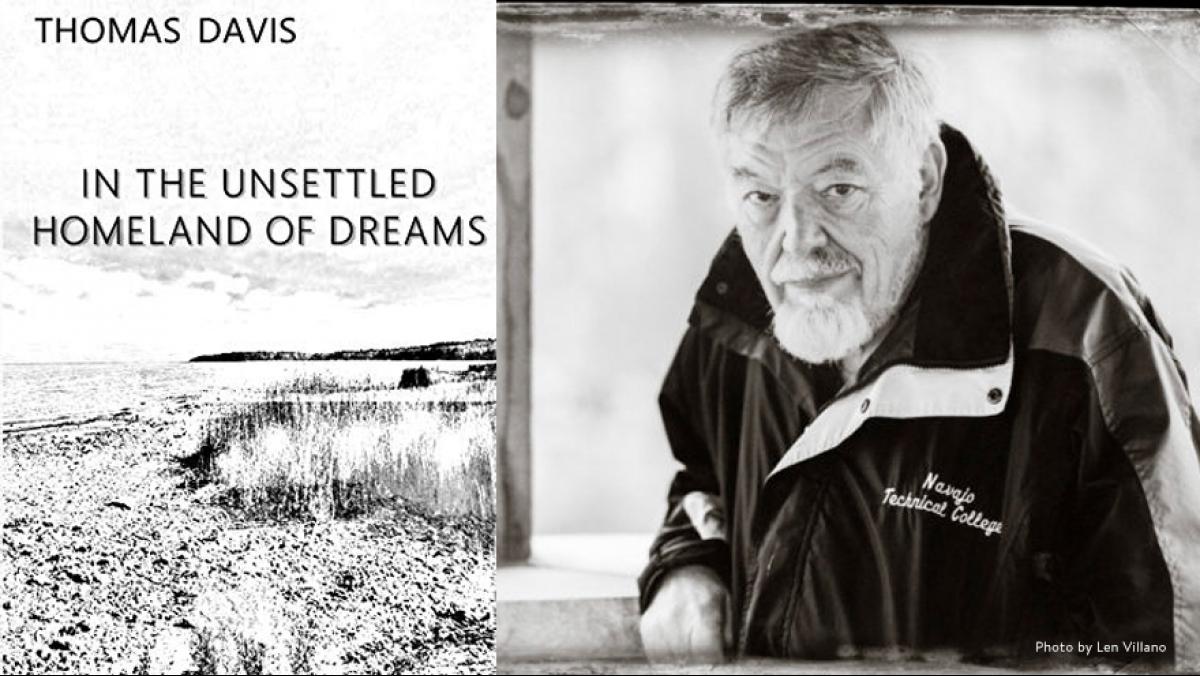

Tourists celebrate Door County’s Washington Island for its majestic scenery and Scandinavian heritage. But Thomas Davis’ new novel, In the Unsettled Homeland of Dreams, reveals the island’s lesser known history as an 1850s refuge for runaway African American slaves. According to Davis, the history surrounding a slave settlement on the island is fragmentary at best. But he was so captivated by the idea that he put aside plans for an academic local history in order to pursue a semi-fictional narrative about the escape of two families from neighboring plantations in Missouri. For In the Unsettled Homeland of Dreams, Davis draws from his own research on the Underground Railroad and escaped slaves to imagine an account of how, with the guidance of two freed slaves, the families make their trek north to the island where they form a community and learn to support themselves as commercial fishermen.

Davis weaves together several narrative elements to create a compelling plot. Readers experience the story from the perspective of the protagonist Joshua, a fourteen-year-old slave for whom the risky adventure serves as a coming of age. Early on in the story, Joshua considers the possibility of escape and a life beyond the fields of the plantation:

He had heard rumors of a conductor on the Underground Railroad whispered late at night in the quarters. Once his best friend, Jamie Bullock, had avowed if he ever had the chance, he would ride the railroad right off the plantation. But Joshua had thought the conductor was supposedly a woman, not a preacher. He’d never asked anybody about the rumors. He suspected now that he not only had not understood what they meant, but that he had thought they were dreams people dreamed after they had been brutalized once too often by the Overseer.

Joshua’s journey to freedom brings him and his fellow pilgrims into contact with idealistic abolitionists and callous runaway-slave hunters, both of whom are dangerous in their own way. The leader of the group, Preacher Tom Bennett, functions not only as a guide for the trek north but also as a community organizer once they arrive on the island. Bennett leads the runaway slaves in their pioneering enterprise in an environment occasionally hostile with unfamiliar weather and not a few antagonistic neighbors. Davis’s realistic description of the slaves’ pilgrimage, along with the accounts of their self-reliance—raising buildings, organizing fishing expeditions, and creating a communal sense of purpose—captivate the reader.

Davis’s novel clearly draws both stories and inspirations from his life-long career serving Native American communities. His accomplishments include helping found the College of the Menominee Nation and serving as president of both Lac Courtes Oreilles Ojibwa Community College and of Little Priest Tribal College. Through his work with native populations, he has become well aware of the obstacles that marginalized people face and the challenges they must overcome.

Davis is also a published poet, and his prose reflects a keen sense of rhythm and timing. He originally considered telling this story through a sonnet sequence, as reported in a recent interview, but ultimately chose prose, utilizing sonnets to introduce and establish a tone for each chapter. This technique serves to underscore the epic nature of In the Unsettled Homeland of Dreams, a well-researched and fascinating tale of how this fugitive slave settlement changed—and didn’t change—the face of Wisconsin’s Door County.