One of the great privileges of working at the Watrous Gallery is getting to know the artists and gaining a fuller understanding of their creative process. In the first few months of the pandemic, not knowing when we’d be able to reopen the gallery, I interviewed Kyoung Ae Cho about the work she had planned to show in fall 2020. Now that her solo exhibition is finally happening (September 9 – October 30), we’re pleased to share this interview with you.

Cho works with fiber, wood, and mixed media, and her art reflects a deep reverence for the cycle of birth, growth, and decay. She starts each piece by mindfully gathering and preparing organic matter and objects of little value, attending to the way their physical properties reveal nature’s language of growth and change. As Cho explains, Each meditative, repetitive gesture, each cut, stitch, and placement is part of the experience of merging the natural and the man-made, the physical and the spiritual.

A native of South Korea, Cho came to the U.S. to study at Cranbrook Academy of Art near Detroit, and taught at Kansas City Art Institute before joining the faculty at UW-Milwaukee’s Peck School of the Arts. Her work has been shown internationally and published widely, and she has been a visiting artist at universities, colleges, and art schools throughout the U.S. and South Korea.

Jody: Thank you for taking time to talk with me, Kyoung Ae. I’d like to start by focusing on your piece Excess I. The pattern was created with crabapple flowers, which you picked after the petals have dropped, is that right?

Kyoung Ae: Yes, so after spring, the petals fall down first and the stems start falling down afterwards.

J: Can you tell me a little about the experience collecting them? Did you collect them in a single season, or was it over several springs?

K: When I collect things, usually I pick one kind of material at a time. I look for something that hasn’t been stepped on, is not squished or out of shape. So I kind of look, pick it up and look around, and like, ‘Okay, you go with me! You stay here.’ You know, kind of pick and choose as I go.

J: Do you have to wait for the right weather? How much planning goes into the collecting that you do?

K: No, I don’t plan. Nature tells me what to do. When things fall, I see and I try to collect. And I don’t have to go anywhere. There’s trees in front of my house.

J: Perfect. So the dates that you gave for this work, 2014-2019, represent a long period. Does that include the gathering? Do you set the blossoms aside for a while? Do you work on several pieces at a time? Tell me why the time period is so long.

K: So, Excess I is actually the first one in this series, and when I work on anything new I spend time to collect the materials first, and then I wash all of them, even though they’re not necessarily dirty or anything. But still, there might be some bugs maybe, so I usually wash it and dry it, then put it in a phone book. I have phone books piling up in the corner that I use for pressing. So I press them for a little bit, and when they get nice and kind of flat and stay in one direction—some of them are twisted, so when that happens, I iron them. So that’s kind of the final situation for the preparation. So once I do that, I start playing around on the canvas or paper or any surface and then start working on it. So I worked on this particular piece first, and then I thought I was done. I saw the result and then I ended up doing another piece and another piece. And then after doing two or three pieces, I was like ‘Oh, I don’t like this first one. I need to do something more’. So I actually went back and added more stiches and added more burn marks. So I reworked it. Does that make sense?

J: It totally makes sense, yes.

K: I even add to the title in some cases, I try to title it like Reworked—I try to be honest. In a way, the whole idea or concept, or the proportion was all finished the first time and the big effort of stitching was in the last year. So I felt like, ‘How do I include this?’ I didn’t mean to say like this was taking forever, but I still don’t want to call it this year or last year only, because I kept going back over the ones that were done before.

J: Do you often work in series like that? Does it depend on how much of a particular material you’ve collected?

K: I do work on series most of the time, and as long as there’s a tree dropping all those petals all the time, I can always collect more. But usually I move on to other things because I discover something else, not because I’m done with it. There’s always a potential to go back to what I was doing. There are certain things that I teach, like specific mediums and techniques. And I stopped using those in my own work for a while because I’m doing something else that excites me more. So I don’t ever think like —‘You’re done.’ Never. You know, I always go back. But I do have a tendency to work in series. For the first one, you have like a big achievement feeling, but when you start working on the second or third, it doesn’t have that discovery process. But you do find a lot of new ways of working or new ways of looking. So I encourage my students: when you do something you like, try to do it at least three times. Five times is a good number—that way you can say this is working good or not working good. Whether you like it or not, don’t ever make the decision after just doing it once because first time is always not giving the clear answer.

The ideal situation is you do something small and you learn and you learn and you’re testing out and then it gradually gets bigger. But sometimes again, a situation happens, like a wooden quilt I made many, many years ago. This brilliant idea came to me, and I had to make this 9 x 9 foot piece without really any prior knowledge. So I had to struggle in making this big one, although it was successful, but I made a small one afterwards to see how much I can improve and discover more. But that was a hard way of learning. You want to do something small to start.

J: That sounds like a really ambitious piece.

K: Sometimes it happens and you have no choice; you just have to do it. You know?

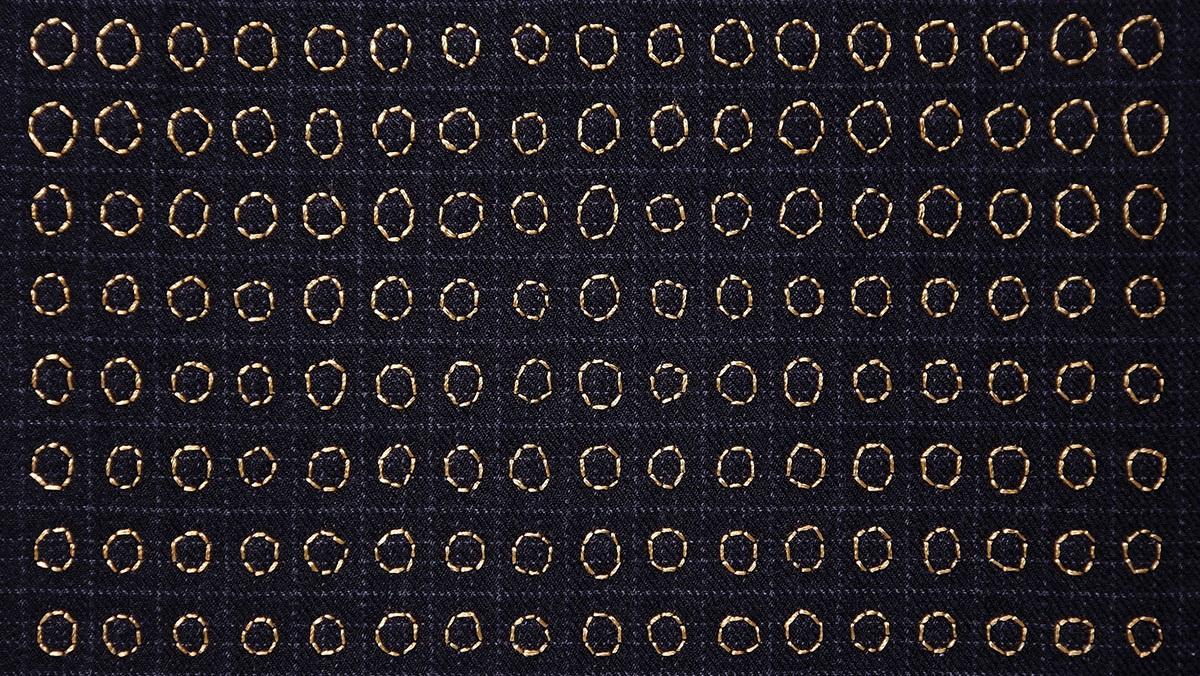

J: For years you’ve used these tiny burn marks on wood and paper and canvas to create pattern. What inspired you to use that technique? Why do you think using these burn marks has had such staying power for you?

K: When I started using the burn marks, I was marking on wood directly, following the wood grain and enhancing the wood grain. You end up thinking, What does this mean?’ ‘Why do I keep doing this?’ So, you squeeze your brain in trying to think ‘Okay, what else is behind this?’ ‘Is there anything?’ I think about harmony a lot and extreme opposites, and yin/yang—that kind of eastern philosophy of how opposite forces are not so good when they are in the wrong situation, but when they are harmonized, they are the best match. So like fire and wood as a match. Wood and fire can be totally disastrous when you don’t have a plan, but it also creates an energy and there’s a lot of great things happening when they’re harmonized. So the mark becomes a beauty mark when it’s. And then also, [there is] the spiritual level of how something becomes nothing. Physical thing becomes spiritual thing. Like with incense, how it burns and then kind of disappears in the air and how people associate that with the spiritual journey. Maybe I’m stretching it out too far, but I think about that as well.

J: I can see correlating that idea of spirituality with this—you’re making this mark by creating an absence, by taking away some of the material by working with the canvas or the wood. But in the end, you’re actually creating a new whole.

K: Right. It’s a beautiful mark to begin with, so the whole process is kind of, almost celebrating. This use of leftover or fallen down parts of natural material, in a way, I see as a kind of finale. They’re at the end of their cycle and they’re on the ground. And I’m just following one more leaf before they become dirt again. So, in a way, the idea of burning incense is part of my thinking as well.

J: That’s beautiful. I really like that idea. Tell me a little about the title, Excess I.

K: So, my English may not be perfect so whenever I try to title, I cannot go too far because I don’t want to misuse a word. I was thinking about the use [of] the word excess—like when the apple tree blooms, they bloom beautifully, right? Like so much flowers. And many fell down – they bloom because they tried to make a fruit, right? But not everything survives to become a fruit, and they all fell down. So, I think about how my mom’s generation, the baby doesn’t survive but they make a lot of babies, you know? You learn to make sure some survive. So that kind of idea, excess, you gather, you have so much, just to be on the safe side. I was thinking of that kind of excess, and whatever is left over, whatever is not used.

J: I just watched My Octopus Teacher. A beautiful film, and as you were speaking I remembered how the octopus gave birth to this amazing number of tiny octopi. And most of them will not survive. I mean it’s true for so many species, but it really struck me watching the birth of this cloud of tiny octopi floating through the water and knowing only a few will actually survive.

K: Yeah, I think even trees really know when something is wrong, and I mean, they bloom. I remember one year that I planted something that only grew 2-3 inches tall, but the winter was about to come and it was blooming like a full-sized flower. It still made the cycle. I guess they will hurry to make it work, even if not fully grown. So I think nature has that kind of survival instinct. Like all of the maple seeds I weed out when they fall, they come up so fast. And it’s just like survival. They must know we’re pulling those out.

J: Absolutely. They would be everywhere if we didn’t do something about it, although I suppose they crowd one another out eventually.

K: Well, they’re supposed to be, right? Cause we cover with concrete and all those things, and we’re taking their space and claiming it so we make it easy for us to live, but at the same time, nature doesn’t know our rules so they just drop their seeds and make their babies and have their blooms.

J: What kind of materials are you working on right now? What are you most excited about?

K: Since I constantly collect, I don’t see lacking any natural materials. But there might be a whole different direction by the time of my show. Because of COVID everyone is home a lot, including me. And you start seeing a lot of things that annoy you, more than before, because you end up noticing a lot more. And because I collect so much, I live alone in my house, it’s becoming this old lady that has piled up things in the corridor. I don’t want to be that way, but somehow, I realize ‘Oh, how come my house is so small?’ I mean, I live alone—where is all my space? So I’ve been going through my closet and cutting apart all my clothing I didn’t wear for a while and couldn’t fit, and I’ve been making lots of little shapes to do an installation. So it’s different from natural material, but it’s a kind of different excess in my house that I’ve been working with now.

J: That’s great. I was trying to keep myself from laughing when you started talking about yourself as an old lady hoarding in the house.

K: Okay for example, I came to America in 1988. Right now, the tank top that I’m wearing I used to wear in high school. And it was still in good shape and it still fits. I was like ‘Oh, I forgot about this!’ And small articles of yarn that I dyed in college. I brought all over here. It’s not even same country. I don’t know why I dragged it here, and I’ve been using it for samples for my students but, see this is why I’m keeping. This is really bad because it proves to me I can be hoarding things because I’m using it.

J: Right, you’re justifying your own practice. I’m curious to see this installation idea with clothing. That sounds really interesting.

K: I’m glad no one’s visiting my house. But I have my own order of things and I’m having fun so it’s okay. Everything has a reason why things are there instead of throwing away. I have object and material—I have all the reasons.