After six months of searching, I stumble upon the last ivory-billed woodpecker the world has ever known.

Though, admittedly, what I find in a file folder at a museum in Wausau, Wisconsin, hardly qualifies as an ivory-billed woodpecker. It isn’t exactly flesh, blood, and feathers, after all. Rather, it’s a seventy-year-old drawing of the last of its kind

And, too, when I use the phrase “the last ivory-billed woodpecker” in describing what I find, I’m asking you to disregard the seven or so sightings of ivory-billed woodpeckers in Arkansas between 2004 and 2005, one of which resulted in four seconds of blurry video proof that the bird still exists.

Or at least proof enough for some.

After sixty years of little more than a handful of alleged sightings, one cool February day in 2004, kayaker Gene Sparling took to the Cache River near Brinkley, Arkansas, and glimpsed a bird thought to be extinct.

He posted a description of what he’d seen on an online message board and was soon contacted by Tim Gallagher, an ivory bill expert and editor of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s quarterly magazine, Living Bird.

Gallagher, accompanied by his friend and fellow ivory bill aficionado, Bobby Harrison, soon found themselves paddling the Cache alongside Sparling for a search that—almost unbelievably—yielded yet another sighting. Gallagher and Harrison watched as the bird darted across the bayou toward a nearby tupelo tree.

“Look at the white on its wings!” Gallagher cried, and Harrison did, confirming the feature that most distinguished the ivory-billed woodpecker from its smaller, commonplace cousin, the pileated woodpecker.

The pair compared notes, and, after corroborating their individual stories, Gallagher called home to report the news to his wife, journalist Rachel Dickinson.

“Had I known then that I was going to have to keep the biggest conservation secret of the past century to myself for almost fourteen months,” Dickinson later wrote in a piece for Audubon, “I might have asked him not to divulge any of the details.”

What happened next seemed more like a Hollywood thriller than a scientific birding expedition. Calls were made, important people were brought “into the know,” and within weeks the New York-based Cornell Lab had partnered with a local chapter of the Nature Conservancy to begin work on the vaguely named “Arkansas Inventory Project,” whose secret mission it was to find further evidence of the bird’s re-emergence.

For fourteen months a tight-lipped group of scientists and researchers continued their quest until April of 2005, when the U.S. Department of the Interior hosted a press conference to announce the Arkansas Inventory Project’s findings.

As the cameras rolled, Cornell Lab director John Fitzpatrick took to the microphone, making clear both the cultural and scientific importance of finding a living ivory-billed woodpecker.

“This is no ordinary bird to the 70 million Americans who are birdwatchers,” he explained. “This Holy Grail is really the most spectacular creature we could imagine rediscovering.”

At the press conference, U.S. Interior Secretary Gale Norton and Agriculture Secretary Mike Johanns gleefully announced a “multi-year, multi-million-dollar partnership” to “aid the rare bird’s survival.”

Scientists and ornithologists cheered the good news—even if, for some, the rare bird’s survival seemed a little too good to be true. Skeptics questioned the accuracy of the sightings, and some even argued that, even if a handful of ivory-bills had been found, the species was as good as extinct in light of the shrinking lowland forest habitat.

We’d tried saving the ivory-billed woodpecker before: first, by way of ornithologist James Tanner’s 1942 book The Ivory Billed Woodpecker, then two years later, through the brushstrokes of a wildlife painter named Don Eckelberry. Though both their efforts would serve as fitting elegies for the soon-to-be-extinct bird, neither man’s work was strong enough to stave off what seemed an inevitable loss of a species.

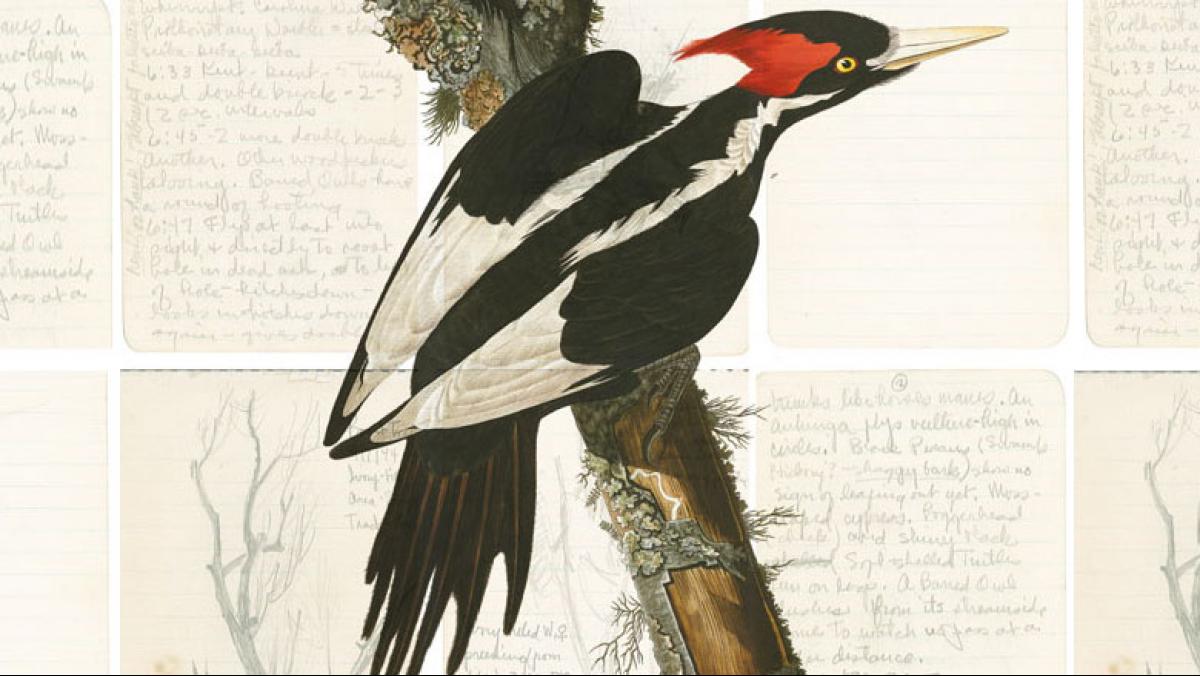

At roughly twenty inches in length and thirty inches in wingspan, the ivory-billed woodpecker is one of the largest woodpeckers in the world. Known for its eponymous ivory-colored bill—not to mention the male’s scarlet crest—it has long been called “the Lord God Bird,” so nicknamed for the phrase often uttered upon seeing its imposing form.

In his early-19th century masterpiece, Birds of America, John James Audubon wrote of the bird’s beauty and power:

It seldom comes near the ground, but prefers at all times the tops of the tallest trees. Should it, however, discover the half-standing broken shaft of a large dead and rotten tree, it attacks it in such a manner as nearly to demolish it in the course of a few days. I have seen the remains of some of these ancient monarchs of our forests so excavated, and that so singularly, that the tottering fragments of the trunk appeared to be merely supported by the great pile of chips by which its base was surrounded. The strength of this Woodpecker is such, that I have seen it detach pieces of bark seven or eight inches in length at a single blow of its powerful bill, and by beginning at the top branch of a dead tree, tear off the bark, to an extent of twenty or thirty feet, in the course of a few hours, leaping downwards with its body in an upward position, tossing its head to the right and left, or leaning it against the bark to ascertain the precise spot where the grubs were concealed, and immediately after renewing its blows with fresh vigor, all the while sounding its loud notes, as if highly delighted.

In their heyday—and by heyday I mean in the 1800s, prior to the removal of 98% of native forest habitat that once covered 24 million acres—ivory-billed woodpeckers were considered “abundant” by Audubon, inhabiting swampland forests from Memphis to Little Rock to Houston and beyond.

Yet the once abundant bird became far less so after the lumber industry began to denude the lowland hardwood forest of the southeastern United States. To a lesser extent, hunters, too, played a role in the bird’s decline by emptying trees for hat feathers or to fill the cabinets of curiosities of wealthy patrons.

As the ivory bill population dwindled, a group of researchers from Cornell University set out in 1935 to gather what information they could about the once-abundant bird. Among the small group was graduate student James Tanner, who dedicated over 21 months and 45,000 miles to tracking the ivory bill.

I imagine it proved to be a mostly thankless task of peering into empty nesting holes again and again. After all that time and all those miles, the only thing Tanner had to show for himself were observations from the same six ivory bills, all of whom took refuge in Louisiana’s Singer Tract, a 130,000-acre swath of ancient forest owned by the Singer Sewing Machine Company.

Despite a lackluster showing by the ivory bills, the research was enough to help Tanner pen the definitive book on the species, rather than, ecologically speaking, closing the book on them altogether. Published by the National Audubon Society in 1942, Tanner’s The Ivory Billed Woodpecker opens with a general description of the elusive bird and offers an extensive profile of characteristics, including its feeding, nesting, and breeding habits as well as the bird’s original distribution patterns and a chronology of its decline.

Through his writing, Tanner would become for the ivory bills what Dr. Seuss’s The Lorax was for the trees: an outspoken advocate. Though Tanner’s tone remains scientific throughout The Ivory Billed Woodpecker, his prose occasionally reflects his frustration and helplessness:

Large numbers are not necessary for the continued existence of the ivory bill. Even though it would be better and more promising if the birds were more abundant, still they are not, and if we are to make any attempt to save the species, we must be satisfied in starting with a few individuals.

Indeed, by 1942 the capacity to increase the number of remaining ivory bills was largely out of human hands. Though, we still had some choice as to what to do next if—as Tanner implied—we decided to do anything at all.

The first time wildlife artist Don Eckelberry came face to face with an ivory bill, the bird staring back was already dead. He was just a boy then, and the rare specimen was a gift to the Louisiana Department of Conservation.

“It was a big woodpecker,” Eckelberry recalled years later, “larger than a crow, strikingly patterned black and white, with a long scarlet crest and a prodigious ivory-white beak.”

What Eckelberry didn’t know then was that in 1944 he would see yet another ivory bill, wild and alive in the Singer Tract, even as the woods were being deforested by the Chicago Mill and Lumber Company. As a result, Eckelberry would hold the dubious honor of being the last person to have a universally accepted sighting of the species.

His eyes were the last eyes to see her eyes, which Eckelberry described as “hysterical” and “pale.”

For years Audubon Society President John Baker had been working on a deal with the Chicago Mill and Lumber Company to save at least part of the Singer Tract. In 1940, Baker asked Louisiana Senator Allen J. Ellender to introduce a bill to establish the Tensas Swamp National Park as a way to preserve a 60,000-acre section of the tract. Baker secured pledges of support for the bill from the heads of the U. S. Forestry Services, the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and the National Park Service. He even received an endorsement for the bill from President Franklin D. Roosevelt. It wasn’t enough.

At a 1943 meeting between Chicago Mill president James Griswold and his counsel and Louisiana wildlife officials, Governor Sam Jones, John Baker, and other interested parties, Griswold bluntly stated that they were not willing to even discuss any plans that would interfere with plans to complete the cutting of the Singer Tract in accordance with their contract rights.

Sensing the probable demise of the Tensas Swamp National Park bill, Baker immediately dispatched Audubon staffer Richard Pough to the Singer Tract, hopeful that an ivory-billed woodpecker sighting might renew public interest.

From early December 1943 to mid-January 1944, Pough spotted only a single female ivory bill.

A despondent Baker sent Audubon artist Don Eckelberry to meet Pough in the hopes of preserving what he could of the Singer Tract female through sketches. For two weeks Eckelberry tracked her, writing and sketching every last detail. He went where she went—taking a boat upriver past Alligator Bayou, then a car to John’s Bayou—and even began loitering around the roost tree, his ear cocked and awaiting the sound of her call.

The ivory-billed woodpecker’s call note is a nasal sound reminiscent of the tooting of a toy horn. Some people refer to it as the “kent” call because it sounds as though the bird is saying, kent, kent, kent.

His first encounter occurred at 6:46 pm on April 5th. There, amid the downy and the red-bellied woodpeckers, came the woodpecker that mattered most, her wings, according to Eckelberry “cleaving the air in strong, direct flight.”

Reaching for pencil and pad, Eckelberry took all the notes that he could, watching her preen, rap, then bounce about the roost hole before entering, exiting, and—after one final five minute flyby—enter her roost for the night.

Eckelberry, who’d taken up temporary residence with a Louisianan he’d pseudonymously named Mr. Henry, could occasionally be found on the back porch alongside his host, watching the deer emerge from the darkened forest. But as his ivory bill searching days wore on, Eckelberry became equally well-acquainted with Mr. Henry’s housekeeper, a woman named Liza who warned him against exploring the forests after dark, that the woods were “full of haunts.”

“But the only spirit I could hear,” Eckelberry wrote, “was the voice of doom for this entire natural community, epitomized by that poor, lone ivory bill.”

Seventy years removed from Eckelberry’s time in the Singer Tract, I make the hundred-mile drive due east from Eau Claire to Wausau to see that bird for myself. Or at least what’s left of her.

I arrive at the Leigh Yawkey Woodson Art Museum—internationally known for its annual Birds in Art exhibition—at a few minutes before 8:00 am and knock on the broad glass door.

The museum doesn’t open for an hour, but my guide, curator of collections Jane Weinke, offers me a private, early morning tour of the galleries. She allows me to linger in the gallery that holds Legacy Lost & Saved: Extinct and Endangered Birds of North America, the exhibition that spurred my visit. The gallery walls are filled with everything the skies are not: passenger pigeons, Carolina parakeets, even the great auk himself.

“What do you hope this exhibition reveals to people? Is there a conservation message?” I ask Jane as we stroll around the gallery.

She ponders this, and says, “I think just by being here, seeing the artwork and reading the extended labels, it gets people thinking.”

I nod my head in agreement, but my eyes are on Eckelberry’s original April 1944 field notes, framed and hanging in two horizontal rows in the corner of the gallery.

“These are them?” I ask, my nose inches from the glass. “His original notes?”

Jane nods as I squint to read Eckelberry’s poetic descriptions of the “vine draped trunks against the blue-green sky” and the “willows standing waist deep in muddy water.” I read also how the “soft-shelled turtles sun on logs” and how the barred owl “flushes from its streamside home.”

But his notes capture more than mere backdrop, and on the page dated April 5th—the day of his first sighting—Eckelberry offers nothing short of a play-by-play of his encounter.

6:33 Kent-kent—5 times and double knock- 2-3

6:45 2 more double knocks…

I already know how this story ends, and yet I read his notes in great anticipation, my eyes running along the ivory bill’s Morse code: kent-kent, double-knock, kent-kent.

I turn my attention to his notes from April 11th:

About 5:30—KENT!

Double rap while walking

Through small uncut

area about 1/3 mile from

rd. Found her immediately.

I reread the phrase that was surely never uttered again—Found her immediately.

“Plenty more where that came from,” Jane says. “We’ve got his sketches, too, right upstairs.”

I turn to her, dumbfounded.

“We inherited quite a lot,” she says with a wan smile.

Upstairs in Jane’s office, several sets of black filing cabinets occupy the far side of the room, numerous drawers of which are dedicated to Don Eckelberry.

“We’ve got just about every letter he ever wrote, and every letter ever written to him,” she says, pointing to manila folders containing correspondences between Eckelberry and any number of artists, editors, and friends.

Tucked into one folder are the sketches I most hoped to see: eight of them, each of which offers a new look at our long-lost girl.

I flip wide the folder, holding in my hands the last-known sketches of the last-known ivory-billed woodpecker. The sketches are rough, though they offer far more visual detail than the field notes hanging in the gallery below our feet. There is her crest, her ivory-colored bill, her wings carefully folded to her sides. In one sketch there are actually two of her; or, rather, two views, Eckelberry managing to double the species’ entire population by way of a few extra pencil strokes.

Though most of his sketches depict the ivory bill on her roost tree, the one I admire most is her portrait; her neck sprung back in perpetual hold, as if preparing to debark a cypress branch. There is the white stripe of her neck, which, if followed, leads directly to her beak.

When Eckelberry drew this ivory bill she still breathed, rapped, had the good sense to fly away. On paper she remains motionless—not a blur or a flash, just an image—as if she’d willingly posed for him.

Though Eckelberry had described her “hysterical pale eyes,” in this portrait all I see is calm. Or resignation, maybe, for a prophecy not yet fulfilled.

I stand in that office for half an hour or so, fully aware that this is likely as close to the Lord God Bird as I’ll ever get. I hear no kent calls, no double raps; just the silence that always comes in between.

Or after.