Trained at Harvard University in the History of American Civilization and conversant with folk traditions in the East, the South, and the West, Dorson found himself ill-prepared for what he discovered during his time in the Upper Midwest. This was not the America he knew: The New England villages, New York tenements, Pennsylvania Dutch farms, Appalachian hollows, Southern cotton plantations, or Western plains celebrated by folklorists and familiar to the nation. Here was a territory of deep woods, inland seas, mines, mills, and hardscrabble farms; a place wherein Native peoples, native-born, and newcomers jostled, jangled, and intermingled to forge Another America.

Fluent only in English and lacking any type of recording device, Dorson relied on interpreters, his own good ear, and a nimble pencil to set down stories. During extended fieldwork in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula in 1946, Dorson documented the oral traditions of “Ojibwa, Potawatomi, and Sioux Indians;” of “Finns, Swedes, Poles, Germans, Italians;” of Irish, French, and English; and of “Luxemburgers, Slovenians, and Lithuanians;” all toiling variously as “farmers, lumberjacks, copper and iron miners, fishermen, sailors, railroaders, bartenders,” maids, cooks, and more.

In the aftermath, he jubilantly proclaimed, “the abundance and diversity of the oral traditions I found still stagger me.” Having thoroughly traversed Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, Dorson ranged briefly into Wisconsin and learned enough about northern Minnesota to recognize their kindred polyglot, egalitarian, working-class frontier ferment.

Yet, important as Dorson’s research was to the understanding of the folk traditions of the Upper Midwest, he completely neglected central elements of this unique culture: the songs they sang and the music they made.

Fortuitously, and unbeknownst to Dorson, a trio of like-minded folklorists had been roaming the Upper Midwest for a decade during roughly the same period—each equipped with a bulky microphone and disc-cutting machine, spare needles, and scores of blank acetate-coated aluminum records—to capture the region’s full span of folksongs in English and otherwise. From 1937 to 1946, Sidney Robertson Cowell, Alan Lomax, and the University of Wisconsin’s Helene Stratman-Thomas, with federal support from the Archive of American Folk Song at the Library of Congress, recorded nearly 2,000 traditional performances in more than twenty-five languages from musicians and singers in Michigan, Minnesota, and Wisconsin.

Captured in kitchens and parlors, churches and dance halls, the recordings made by Cowell, Lomax, and Stratman-Thomas spanned dance tunes, ballads, lyric songs, hymns, laments, political anthems, street cries, recitations, and more.

Many recordings held sonic fragments of lost worlds: a Missouri-born ex-slave’s comic commemoration of Noah’s Ark; an Icelandic mother-daughter duet concerning a Christian knight enticed by cliff-dwelling elves; an exuberant calling of the clans by a Scots-Gaelic émigré.

Other recordings featured dramatic adaptations of esoteric indigenous and Old World repertoires for then contemporary public events: a Ho-Chunk warrior song repurposed for summer tourists; a Finnish lullaby arranged for the stage of a workers cooperative hall; a Norwegian one-stringed solo church instrument used by a quartet to play secular tunes for multi-ethnic culture shows.

Some were well-known 19th century patriotic songs reinvigorated from afar with 20th century despair and rage as invading Fascists occupied Lithuania, the Netherlands, and Norway. Still others addressed new circumstances through witty or poignant makeovers of familiar genres: an Italian sojourner’s paean to America’s grandeur; an impoverished Polish immigrant’s lament for a family whose passage to America he can never pay; a former Czech soldier’s song transposed to Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin.

A handful of recordings included scurrilous or bawdy ditties previously ignored or censored by genteel folklorists: a Finn’s versified lashing of cheating merchants; a lumberjack’s rasty condemnation of biscuits that “would make an ox fart”; an alphabet song commencing with “Oh A is for asshole.”

And there were startling mash-ups of languages, genres, and cultures: Ojibwe hand-drum songs rendered on fiddle; a Finnish sailor’s homesick lyric sharing its tune with the cowboy song “When the Work’s All Done This Fall”; “The Irish Washerwoman” played on accordion by Germans chanting square-dance calls in English; a Quebecois mixed-language ditty about a bumpkin’s misadventures in Michigan.

Songbooks, radio, and 78 rpm recordings in many languages likewise circulated throughout the region at the time, with lyrics and melodies added to those learned from oral tradition alone: a ballad sung verbatim from a Danish folk-school songbook; a version of “Gambler’s Blues” acquired from a Paramount 78 rpm cut in Grafton, Wisconsin; Gene Autry’s “Three’s a Gold Mine in the Sky” harmonized by Polish sisters who had heard his broadcasts over WLS-AM Chicago’s National Barn Dance.

It’s important to note that these performances were captured in all their variety and complexity at a significant historical moment: America was in the throes of the Great Depression and World War II was erupting in Europe. Market-driven mass culture was developing as a national force, and concerns with who and what was “American” dominated the media of the day. Up until the past couple of decades, the pursuit of cultural plurality held little or no value for the American government, academic institutions, or popular culture as a whole.

As such, the books and record albums of Sidney Robertson Cowell, Alan Lomax, and Helene Stratman-Thomas exclusively emphasized English-language performances; it was as if the majority of the songs they recorded simply did not exist.

Despite the efforts of these three incredible folklorists—none of whom were the “narrow specialists” of Dorson’s admonition—the folksong traditions of the Upper Midwest have for years remained largely elusive and almost forgotten.

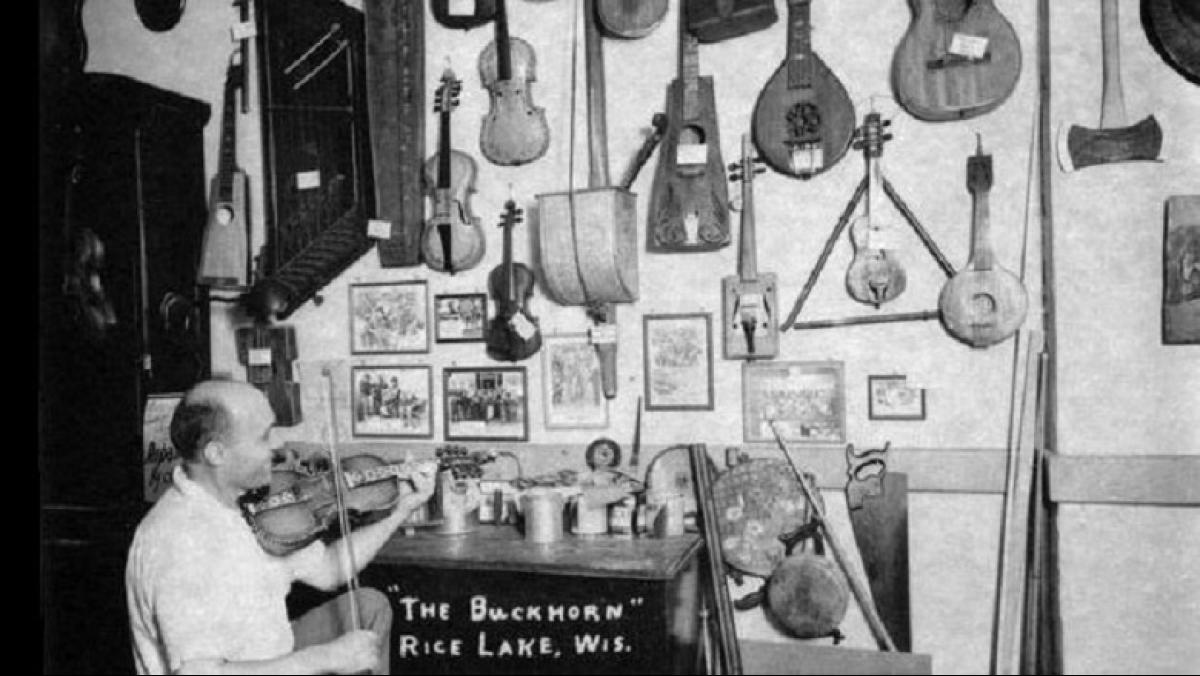

My own discovery of our region’s folk music ferment began in the early 1950s in Rice Lake, Wisconsin. It was summer, and Art McGrath—Warren Leary’s college pal, fellow combat veteran, and best man at his wedding—had come north from Indiana to see my dad in his hometown. The two set out for a drive, a hike in the woods, and a beer. Rather than leave my mom at home with four mischievous kids under age six, Dad took my older brother and me along. Our final destination was the Buckhorn, a bar and café on Rice Lake’s Main Street famed for its Display of Curios. While Art and Dad secured barstools, sipped Breunig’s Lager, and swapped stories, Mike and I, clutching bottles of pop, roamed the checkered floor and gaped.

Mounted heads of moose, bear, and deer, whole wild cats, weasels, birds of prey, and fish festooned the walls. They mingled with fantastic mutant creatures: the owl-eyed ripple skipper, the fur fish, the dingbat, the shovel-tailed snow snake. There was a slot machine, a thick pockmarked, bulletproof windshield from Al Capone’s car, and best of all, occupying an entire wall, “the world’s largest assortment of odd lumberjack musical instruments”: guitars, mandolins, and fiddles fashioned from cheese and cigar boxes, an elongated tin trumpet, a steel triangle, a bowed saw, a single-string bass fiddle cobbled from a shovel handle and a flour bin, a pitchfork fitted-out similarly, and more.

“Otto Rindlisbacher and some of those old lumberjacks made ’em,” Dad explained, sweeping his hand toward the bald proprietor and a handful of wool-clad old timers along the bar.

My visits thereafter to the Display of Curios were few and fleeting until the mid-1960s, when, employed by the weekly Rice Lake Chronotype, I delivered bundled newspapers to a throng of Buckhorn patrons. The instruments were still there, and I learned from my dad’s sister—Katherine Leary Antenne, “Aunt Kay”—that Otto played them all and had even made records for the Library of Congress in Washington DC. What’s more, while attending that city’s Trinity College, she had seen him perform with the Wisconsin Lumberjacks at the National Folk Festival of 1938.

Too young and shy to approach Otto and ask him to play, I finally heard his music around 1968 when, prowling Rice Lake’s Carnegie Library in search of folksong records, I came across a plainly packaged LP produced by the Recording Laboratory of the Library of Congress, Music Division: Folk Music from Wisconsin. Inside were four tunes from Otto, a fifth from his wife, Iva, and rich notes cheaply offered in a stapled typescript. From these notes I learned that someone named Helene Stratman-Thomas had traveled Wisconsin in the 1940s recording performers for the Library of Congress.

By the mid-1970s I was a young folklorist myself, and lucky enough to work in Washington DC for the Smithsonian Institution’s summer-long bicentennial Festival of American Folklife. The Library of Congress beckoned. On a day off, I visited its Archive of Folk Song for the first of many times. Aided by archivist Joe Hickerson, I discovered the broad scope of Stratman-Thomas’s Wisconsin recordings, that Rindlisbacher had not only recorded for her but also for Sidney Robertson and Alan Lomax, and that the Upper Midwestern work of all three—from 1937 to 1946—was interconnected.

From the 1980s through the mid-1990s, as a folklorist working in my home region, I happened onto the fieldwork trails of Robertson, Lomax, and Stratman-Thomas with increasing regularity. In 1981, for example, an octogenarian retired streetcar conductor and piano accordionist in Ironwood, Michigan, John Shawbitz, remembered “some guy from Washington” recording his Slovenian tunes in the 1930s. Elsewhere in Michigan, the daughters of Exilia and Mose Bellaire recalled their teenage excitement when good-looking Alan Lomax recorded mother, dad, and assorted French neighbors in their Baraga home. In 1989 Ed Kania and the brothers Jake and Joe Strzelecki had similar recollections of their fathers recording for Lomax in Posen, where Sylvester Romel, the lone survivor of a singing family, wept as he listened to and sang along with a duet performed fifty-one years earlier with his late brother.

In Wisconsin, Lois Rindlisbacher Albrecht told me about her parents’ preparation for the 1937 National Folk Festival, where Sidney Robertson recorded them. She and Al Mueller described how, three years later, Stratman-Thomas captured Swiss tunes from them, while Ken Funmaker Sr. and Olwen Morgan Welk offered childhood recollections of their respective Ho-Chunk and Welsh elders being recorded by Stratman-Thomas in the 1940s. And Al Vandertie was still singing Walloon songs when I met him at a Belgian Days parade in 1990.

Bit by bit, I began to wonder about the lives, experiences, songs, and tunes of other Upper Midwesterners documented on discs in the 1930s and 1940s.

It turned out that my curiosity concerning bygone regional field recordings was shared.

In the 1970s, seeking source materials, playwright Dave Peterson, director of the Wisconsin Idea Theatre at the UW–Madison, worked with the UW’s Mills Music Library to secure reel-to-reel copies of Upper Midwestern field recordings of Cowell, Lomax, and Stratman-Thomas from the Library of Congress.

In the early 1980s, Judy Woodward (now Judy Rose) of Wisconsin Public Radio’s Simply Folk set to work on a thirteen-part series, The Wisconsin Patchwork, highlighting selections from the Stratman-Thomas recordings. Having consulted on that project, I was hired by Peterson to write commentaries on each installment, resulting in a booklet published in combination with cassette reissues of the WPR series.

Gradually, foolishly, I began to imagine a project in which I would pull together the recordings of these three pioneering folklorists, still only dimly aware of the challenges of restoring sound on deteriorating discs, deciphering songs in more than two dozen languages, tracking down biographies of hundreds of scarcely documented performers, and determining the often murky provenance of as many songs and tunes.

The result of this foolish notion is Folksongs of Another America, a redemptive countercultural project recalling and honoring the efforts of Cowell, Lomax, and Stratman-Thomas while illuminating the nearly but not quite lost singers and dancers, songs and tunes, individuals and communities characterizing America’s Upper Midwest in the mid-20th century.

Soon to be published by the University of Wisconsin Press and Dust-to-Digital as a multi-format package, Folksongs of Another America presents 187 representative and digitally restored performances by more than 200 singers and musicians, offered on five compact discs and a film/DVD. The accompanying book provides an introduction, full texts of all lyrics in the original languages and in English translation, extensive notes about each song and tune, biographical sketches and photographs of many of the performers, and details about Cowell, Lomax, and Stratman-Thomas and their fieldwork efforts as song collectors.

Looking at and listening to the full extent of this region’s vibrant songs and tunes effectively challenges and considerably broadens our understanding of folk music in American culture historically. Just as importantly, historical evidence of the Upper Midwest’s multilingual singing citizens reminds us that the voices and songs of present-day Bosnian, Hmong, Mexican, Somali, Tibetan, and other immigrants and refugees are an enduring and valuable element of our regional and national experience.