In his seminal book on landscape painting, Kenneth Clark writes that “we are surrounded with things which we have not made and which have a life and structure different from our own: trees, flowers, grasses, hills, clouds. For centuries they have inspired us with curiosity and awe. They have been objects of delight. We have recreated them in our imaginations to reflect our moods.”

And eminent art historian, Clark examined and wrote much about historic landscape painting styles. An Englishman with an orderly mind, Clark devised a few classifications for these styles—“the landscape of symbols,” “the landscape of fact,” and “the landscape of fantasy”—that he hoped would shed light on to what uses landscape imagery has been put over the ages.

Clark wrote that already by the 15th and 16th centuries artists had moved beyond symbolic landscapes drawn from Christian philosophy and into realism. At the time, a burgeoning merchant class fueled the craze for realist landscape painting with expressive compositions and strong contrasts of light and color.

But artists like Albrecht Altdorfer and Hieronymus Bosch felt that landscape art had become too tame and domesticated. They set about exploring the mysterious and the un-subdued, giving birth to a style that we today think of as Expressionist Art. For Clark, more recent expressionists like Vincent van Gogh, Max Ernst, and even Walt Disney exemplify this spirit of using landscape forms to express a range of emotions—disquiet and wonderment among them.

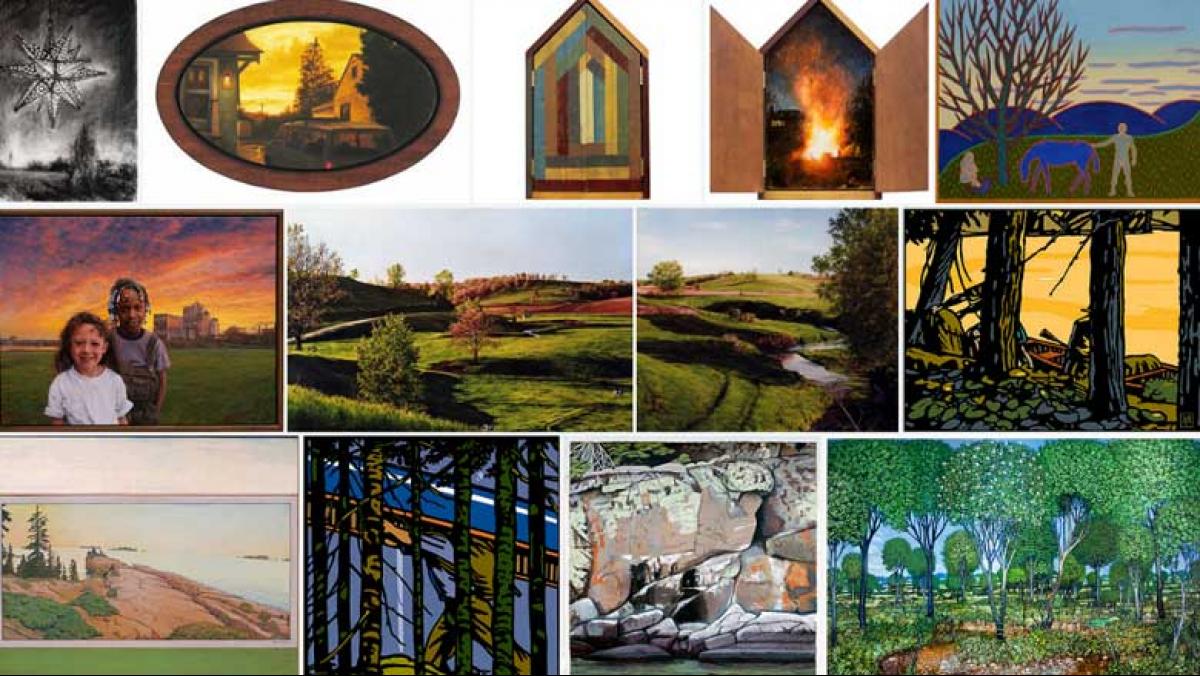

So it was that James Watrous Gallery director Martha Glowacki and I had for some time discussed the idea of curating an exhibition of Wisconsin painters who are landscape expressionists of different kinds. The artists we brought together for our recent Inhabited Landscapes exhibition (click here to see a slideshow of the images from this exhibition) may not easily fall into any of Kenneth Clark’s classifications, but they all adventure beyond mere topographical rendering. Martha and I as curators wanted to play with the idea of landscape art being “inhabited” by artists’ subjective states—mood, memory, dreams—as well as their ideas. The artists included in this exhibition all use their own visual language to create personal visions, unique ways of imbuing the natural world with meaning.

Tom Uttech’s art is literally inhabited by memory. Uttech is passionate about spending time in the woods, leaving behind his everyday life to wander and look. His depictions of a radically wild Northwoods—northern Wisconsin and up into Minnesota and Canada—are not painted out of doors in a specific place (that is, he does not take his paint and brushes there). Rather, Uttech absorbs the atmosphere, the texture, and the light. He then returns to his studio to make paintings without preparatory drawings direct on the canvas, finding the shapes of wildness from memory. Working this way results in more powerful images, he says, eliciting more drama and connection with the mysterious moods of a fictional but naturally convincing wild place than would be possible by sitting outside and copying a tree.

Uttech grew up near Wausau, and he has spoken of a childhood visual epiphany, a magically pure event: the startlingly vivid appearance of a redwing blackbird flying above a green hay field. This memory of a colorful, natural otherness is emblematic of his life as an artist, where his love of bird life—as well as the other creatures of the Northwoods—helps Uttech transform them into messengers of the mystery of wildness. This is a world that humans cannot manufacture, and Uttech puts no human figures in his paintings because he wants to make space for the viewer to enter the painted landscape. Using Ojibwe (Anishinabe) words for his painting titles, Uttech immerses his art in the ancient life of places that have no names.

Much of John Miller’s art also comes from Northwoods wilderness areas. He has spent time as an artist in residence on Lake Superior’s Isle Royale, absorbing the spirit of that special place. Where Uttech paints in a style that is lush and romantic, with echoes of the 19th century Hudson River School, Miller has developed a system of signs to describe the essence of natural forms. Miller’s work as a graphic artist has schooled him in the power of design, and some of his paintings share elements of Japanese woodblock prints. Nature speaks through his artist’s shorthand to translate the landscape’s infinite variety into patterns, texture, and color that resonate with the ancient energies of rocks, trees, and water. The message is a visual ordering that transforms what might look like randomness into an exquisite, perfectly natural orderliness. With his art Miller is our intrepid guide to those wild places he knows; we can trek into the woods or ride along in his canoe.

Charles Munch’s paintings—like Miller’s—make a virtue of simplification. He has over the years developed a highly personal visual vocabulary of flat color pattern and stylized form that projects feeling and mood. Early in his career, Munch painted in a representational style using illusionist space and traditional figure anatomy. By the early 1980s he felt the need to make his work more emotional and expressionistic, closer to what was going on in his personal life. Munch began searching for a formal system that would allow his personality to inhabit his art. Color and a distinct geometry of landscape forms came together to merge feeling and description. Munch is a consummate colorist, using color in his work to create space and light and tune each painting to sing in its own key. Each painting is a unique adventure in design, encapsulating sometimes-dramatic and sometimes-subtle action. His narrative themes, often presented in ambiguous or mysterious imagery, nevertheless speak clearly of his concerns about the “civilizing” tendencies of humans and their destructive effects on the natural environment. This worry, however, is tempered and redeemed by his art’s luminous celebration of life.

Dennis Nechvatal’s art is the product of the artist’s deep immersion in a private world of landscape meaning. He became enchanted with nature during his youth growing up in Lancaster, Wisconsin, in the 1950s. Nechvatal experienced bucolic boyhood days: riding his bike over the rolling sun-dappled roads, fishing pole over his shoulder, and lounging for hours in the shady thickets on the banks of a trout stream. Many years later, Nechvatal has arrived at an art language that celebrates natural forms in what at first appears an idiosyncratic and primitive style. Only by surrendering to the emotional logic of Nechvatal’s busy world of color and design can one visit his delightful wonderland. Like other artists in this exhibition, Nechvatal is a close reader of art history and theories of perception. The result is the transformation of an everyday view of landscape into an alternative reality where feverish concentration on detail, a sharply focused definition of otherwise soft forms, and sparkling color beguile the eye and lure viewers into this green space humming with nature’s secrets. In Nechvatal’s world, the trees, flowers, and rocks can become figurative elements—energetic primal effigies promoting affection, awe, and maybe a little fear as to what surprises nature has to offer us.

Living on Madison’s east side, Barry Carlsen has found some of his landscape subject matter in his neighborhood’s backyards and bike paths. He has always been interested in the ways that nature coexists with built environments. Carlsen grew up in Omaha where he became intrigued with old industrial warehouse architecture. His family vacationed in northern Minnesota, where he was also imprinted early on with the magic of the water and the woods, the campfire, and the muskie lurking in the lily pads. Memory is embedded in all his painted landscapes whether urban or Northwoods, and familial narratives are at home in both places. The search for an emotional home gives his work physical shape, and luminosity brings it to life, animating his visual autobiography. Carlsen has said that he uses light as a unifying element in his paintings to heighten the emotional level of the work. Light from an unseen source and the transition between night and day intrigues him. He is interested in human scale in the environment and context’s effect on objects and their meanings. Whatever the content, he sees the paintings as “emotional vignettes,” rather than formal landscapes. They represent visual remembrances; the artist paying homage to place and time.

Landscape art can be inspired by the poetry of exotic places, but it can also come from an everyday source. Cathy Martin is a farmer as well as an artist who has a lifelong connection with the rolling countryside near Prairie du Chien. Her hands-on experience with the land lends her art an authenticity that results in imagery that goes beyond picturesque recording. Her recognition of the beauty of fields formed by good stewardship of the land—as well as her knowledge of what is required to raise a crop and conserve the soil—makes her a natural interpreter of her home ground. Self taught as an artist, Martin instinctively composes her paintings in ways that invite the viewer to stand where she stands, to feel the ground beneath the alfalfa. These are pretty places, to be sure, but they also grow the hay that feeds the cattle. Appreciation of the patterns of this singular landscape, as well as its weather and seasonal moods, makes a satisfying life for Martin and her family—and some incredibly beautiful landscapes.

David Lenz lives in Shorewood, Wisconsin, and some of his subject matter comes from places in and around nearby Milwaukee. Another important source of inspiration for Lenz is the landscape of Sauk County in southwest Wisconsin’s Driftless Area where he and his family own a hilly piece of land next to a small, traditional dairy farm owned by Erv and Mercedes Wagner. Lenz became close friends with the Wagners and documented their work and their lives on the canvas in loving detail. Lenz has also portrayed his son Sam, who has Down Syndrome, in that farm landscape for a portrait that won first prize in the Smithsonian’s prestigious 2006 Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition. He has also painted portraits of children of different races who live in Milwaukee’s working class neighborhoods. In these varied subjects that he calls “the three legs of my painter’s stool,”—farm life, people with disabilities, and inner-city youth—Lenz honors the dignity of his subjects in whatever circumstances he finds them. Regular people in regular places commingle in a painting style where realism is so stunningly heightened that ordinariness becomes spiritual. Landscape, urban or rural, is always the surrounding for David Lenz’s art. In all their glowing naturalistic detail, his paintings become a transcendent setting for people in their places who might not otherwise be celebrated.

For me, the Inhabited Landscapes exhibition is as much a celebration of nature that delights and intrigues as it is a collection of diverse perspectives on the natural world that provoke questions about the role of nature in our lives. In the work of seven fine Wisconsin artists with different life experiences with the land, we have seven individual visual narratives of how we all inhabit a landscape of our own perceptions. Exhibitions like this inform our own sense of place and give us plenty to think about when it comes to recreating nature on a canvas.

Indeed, ideas about “landscape into art” in this postmodern age are as complicated and varied as they were for Kenneth Clark writing on the topic in the middle of the last century: They can run the gamut from an innocent and friendly nature scene all the way to a lurid rendition of environmental apocalypse, spawned by anxieties over what we humans have wrought on this planet. The work in Inhabited Landscapes falls in diverse and rewarding ways between these two extremes.

And yet for many of us the beauty and grandeur of nature is all mixed up with concern about what the weather will do to us next, whether the oceans will rise, and whether we will still be hearing the meadow lark’s song from that pasture fence post a few years hence. More and more folks walk down the street looking at the digital device in their hand, not seeing the spectacular panorama of blossoming cumulus clouds in the startlingly blue sky overhead or (apparently seen only by this writer) the Cooper’s hawk’s dramatic swoop at a hapless popcorn-eating sparrow on the Capitol lawn in downtown Madison. So many of these messages of natural wonder are not being received when we submerge ourselves in virtual realities.

But we share in common the environment that sustains us all. Having seen landscape made into art in the gallery and on these pages, we might all go outside, eyes and minds stimulated, to notice more—and to value more—of what is all around us in the city as well as in the country.