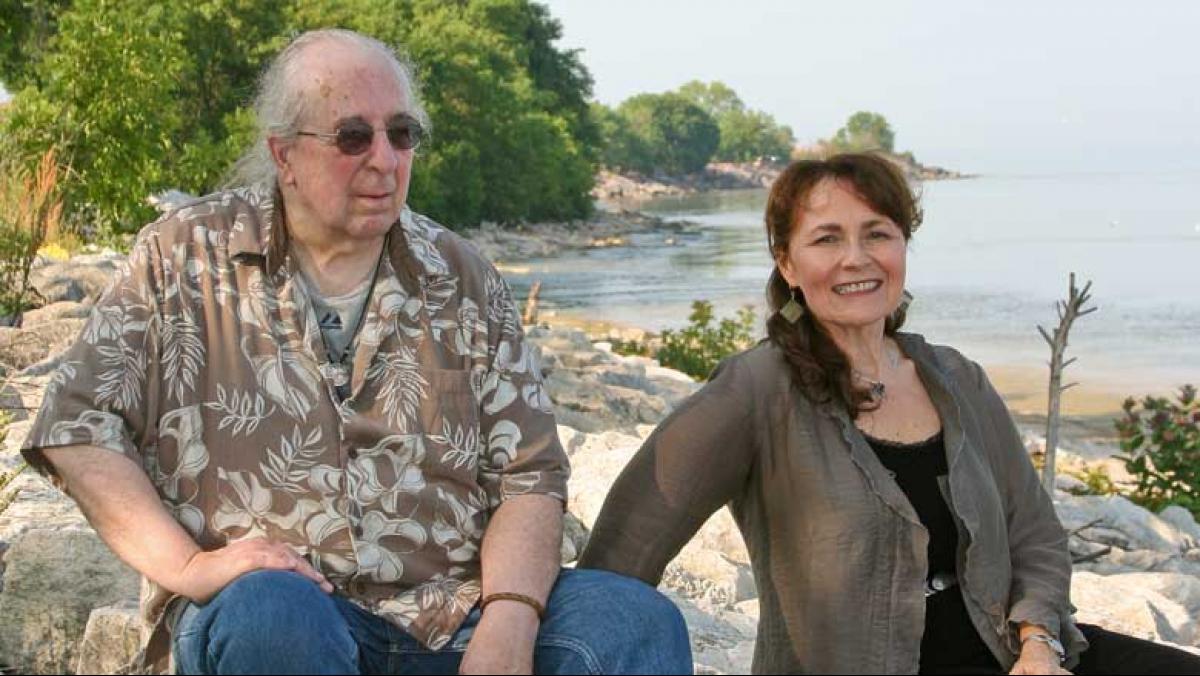

For years Jim Stevens and Kimberly Blaeser have promoted the exploration of poetry and creative writing among Native American peoples, fostering expression and examination of Native culture through the written word in formal and informal courses here in Wisconsin and in publications read around the world.

Stevens and Blaeser collaborated on bringing to Wisconsin in fall 2012 the leading North American Native writers’ festival known as Returning the Gift (RTG). Using the Ojibwe word from which it is believed Milwaukee took its name, ominowakiing (usually translated as “gathering place by the water”), organizers have tagged the historic event A Gathering of Words at the Gathering of Waters. This year’s festival marks the twentieth anniversary of the first RTG writers’ festival held in Oklahoma in 1992, five-hundred years after Columbus’ discovery of America. Held in Milwaukee from September 5–9, the 2012 RTG festival features workshops and readings with internationally known Native writers Joy Harjo (Muskogee) and Joe Bruchac (Abenaki) and hosts a full schedule of public events with other Native writers as part of the 25th Annual Indian Summer Festival at the Milwaukee lakefront.

Literature from Native peoples is one of our oldest and most significant treasures, yet many Wisconsinites can’t name a single Native writer from Wisconsin let alone one from North America. Wisconsin People & Ideas recently had the opportunity to discuss with two of Wisconsin’s prominent Native writers the state of contemporary Native writing, the significance of the forthcoming Returning the Gift festival in Milwaukee, and the past and future of the Native literary journal Yukhíka-látuhse.

How would you characterize Native writing at this moment in time?

Stevens: In general, most people have a limited sense of the nature of Native American writing, just as there is a limited view of Native cultures. Native writing has traditional storytelling at its base, and it contains soul and heart to a wonderful degree. You really can’t divorce the approach to Native writing from all the myriad issues that affect Native peoples today. For example, we did an issue of Yukhíka-látuhse that focused on the mascot problem and featured a collaborative poem by Barbara Munson and me. The poem uses the legislative testimony that eventually led to the passage of Wisconsin Act 250 [Editor’s note: passed in 2009, Wisconsin Act 250 allows a school district resident to object to the use of a race-based nickname, logo, mascot, or team name by the school board of that school district by filing a complaint with the State Superintendent of Public Instruction] and contains the same concerns and language that one would find in a lyric written by a Native writer. It comes down to this: there really is a limited understanding in the larger community of what Native peoples think and do, even in this day and age, and that’s unfortunate. Because of this, we hold it as our responsibility in Yukhíka-látuhse to carry that understanding to the reader.

Blaeser: When I began putting together Contemporary Native Literature classes in the late 1980s, I could manage to offer a fairly comprehensive view of the major Native writers in a survey class. Today I can barely scratch the surface in one course. Publishing in Native literature has simply blossomed. In a lengthy essay I wrote on poetry for The Columbia Guide to Native Literatures of the United States Since 1945, I included a bibliography of one hundred Native poets from the U.S. who had published at least one book. That was in 2006. Now, six years later, I could easily add twenty-five to thirty new Native poets. And that’s writers in only one genre. The volume of writing that is coming out of tribal communities is immense.

The first Returning the Gift festival had a lot to do with this flourishing. It put Indigenous writers in contact with one another and set up organizations like Wordcraft Circle and the Native Writers’ Circle of the Americas that continue to expand those connections into broader networks. Those organizations ran book competitions and created an unofficial clearinghouse for all things related to Native writing. My own first book, Trailing You, is an example of the many publications that, directly or indirectly, can be traced to the original RTG back in 1992.

Around this time, publishing and performance venues also began to be shared more widely, and Native writers began to establish a place for their work in mainstream conferences. International (or, as I like to say, “inter-indigenous-national”) ties began to grow as well. For example, the publications of Theytus Books and Kegedonce Press regularly include the works of Native writers from the U.S. as well as those of First Nations writers from Canada.

Of course, Native writers still face challenges like stereotyping and pigeonholing, obstacles similar to those faced by writers of other so-called “minority” literatures. Many tribal traditions have been generalized and romanticized into a popular image. Accompanying this image is an idea of what “Indian” literature should be. If the work of an Indigenous writer fails to include the expected characteristics—“stoic Indian,” check; “tragic outcome,” check;—it may be deemed inauthentic.

There is also a struggle for legitimacy within the academy and the publishing industry, both of which often marginalize Native writing as simply “ethnic” literature. Where does it fit? Work from Native writers tends to be included in special issues of journals and in designated series of publishing houses more readily than in the regular stream of published works. And it seems that submissions more obviously arising out of Native identity tend to get the most attention. Still, great strides have been made in publishing, promotion, and recognition of Indigenous work.

What roles do you see for Native writing in American society? Does it, for example, work against stereotypes? How does Native writing about Indigenous peoples differ from non-Native representations?

Stevens: I often think of the words of Chief Oren Lyons of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy. He said that we have seen the sun come up in the same place for many thousands of years. He was, of course, talking about a Native perspective, which has to do with knowing so deeply the place some of us call Turtle Island. Native peoples have built up a reservoir of tradition and a body of thought that comes about through an intense relationship with the same earth-space for such a long time. This is reflected in the traditional stories and sacred songs, which are really about this relationship. It is this long tenure in the hemisphere that makes Native writing so valuable, so important to be passed along.

As somebody who grew up around Milwaukee, grew up as “urban Indian,” I can’t know the level of intensity felt by people who grew up on reservations about the use of Indian mascots. What I do know, though, is that “mascots” are stereotypes. That is all they are: ideas that have no basis in reality. What we can really know about Indians, and what is accessible to the dominant culture, can be found in Native writings.

I think of an anecdote told by Mohawk spiritual leader Tom Porter that reflects the way I think of Native writing. Porter tells how, when he would return home from travels within the larger world, his grandmother would sit him down and comb his hair. She would actually be combing the “snakes,” the emotional tangles, from his hair. This is a very loving act, and one that is standard practice in his family. It reflects a perspective in Haudenosaunee tradition of conciliation, one that goes back to the ratification of the Great Law of Peace, the Six Nations compact forged in 1142. It’s also the way I think of writing, particularly Native writing: Native writers carry the deep experience of their lives in American society; some of this is historical, some more personal. The act of writing for Native writers is a way to comb the tangles from our hair.

Blaeser: I love Jim’s description of “combing the tangles" from our hair. Interestingly, someone else who shares his name, a Mohawk writer named James Thomas Stevens, published in 2002 a book entitled Combing the Snakes from His Hair. His title alludes to a similar Iroquois story of healing. Apparently the leader of the Onondaga, Atatarho (pronounced addadarho), was cursed with a crooked body, and his head was covered with snakes. Healing for Atatarho meant both his mind and his body had to be straightened or, metaphorically, the snakes combed from his hair. Press copy for the book states, “Similarly, during the writing of these poems, Stevens experienced a healing, a setting straight of his life and a setting straight of the record.”

An important element to consider when thinking about Indigenous writing involves the use (or what I call the “supra-literary intentions”) of the Native literary arts. In Native traditions, poetry, story, songs, drama, and so forth all strive to be beautiful works of art. But these expressions also attempt to do something in the world—to heal, teach, protect, invoke spirits—as well as entertain. They have both affective and effective intentions. For example, one of the individuals we have invited to participate in the RTG festival, John Purdy of Western Washington University, worked with the Lummi people of Washington State when the tribe faced repatriation issues. When certain tribal members had to dedicate days and months of their time to sifting through disturbed and removed earth in search of tribal remains, Purdy coached them in writing as a means of helping them deal with the trauma and as a way to share their experience with their community.

Sometimes this aesthetic of utility as well as beauty runs counter to certain Western notions—the idea of poetry for poetry’s sake, for example. Native writing as resistance writing is not always valued as “good” literature. But Native authors continue to use their written works as tools of decolonization while simultaneously working to create aesthetically pleasing literary art.

Other interesting issues we might discuss in looking at Native writing at this point in history include Native language use, challenges to traditional genres, differing target audiences, and, as the question suggests, representations. The latter is perhaps the most controversial. Popular and marketable images of Native peoples don’t always portray the true experiences of tribal nations in the Americas.

If absolved from reinforcing the popular notions of Indian and Indian story, Native writing can offer literary innovations as well as unique and enriching perspectives on everything from history to holistic living. Intergenerational stories, a place-centered model of being, survival humor, ceremonial living, earth knowledge, and the tradition of peace-making in legal disputes are all among the life ways woven into these literary works.

How did Yukhíka-látuhse get started?

Stevens: The Oneida Nation Arts Program initially put together a monthly reading series at Norbert Hill Center in Oneida, at the urging of an Ojibwe writer named Ed Two-Rivers, who has since passed away. Ed had been born in Ontario, in an Ojibwe village among the lakes northwest of Lake Superior. He had just moved to Green Bay after many years in Chicago, where he was a founder of Red Path Theater and a playwright, poet, and activist for Native rights. He was skilled in arts administration and a charismatic reader, and he was always invigorating to be around. It would be great if he were still with us.

After the readings ran their course, I suggested to Beth Bashara, the director of ONAP, that we create a magazine to keep the program going. Soon after this, Tinker Schuman—who is a poet, pipe-carrier, and Lac du Flambeau tribal elder—and I started teaching writing workshops on the reservations. We now hold two or three each winter, and we include anyone—elders as well as young people—who wants to come and write. The workshops are very informal, like little get-togethers of people with like interests. We have lunch, then do writing exercises, and read from our ongoing works.

The magazine is a direct outflow of these get-togethers. We came up with the name Yukhíka-látuhse because we decided it was appropriate to give the magazine an Oneida name. The word means, “She tells us stories.” And it’s a wonderful description of the view of communication that Native peoples have: they see individuals as the conduits, rather than the sources, of stories, of creativity. I feel the magazine is a reflection of this.

I am often delighted by the exciting pieces people bring to our gatherings. I will say that we have been fortunate to have ONAP supporting us, and the Wisconsin Arts Board has been very interested in our program and very supportive since the beginning.

So, how does Yukhíka-látuhse fit in with the upcoming Returning the Gift festival in Milwaukee?

Stevens: The idea for the festival started a number of years ago. A group of us connected with Yukhíka were sitting in a restaurant, and Tinker Shuman suggested that we have a general, statewide conference for Native writers. My first response was, I’m just too old to do that! But I started thinking about it and slowly began putting together a plan. In early 2011, I started calling people and trying to arrange something.

Then in February 2011, there was a huge reading of Native writers at the Woodland Pattern Book Center in Milwaukee. It was organized by actor/playwright/poet Thirza Defoe of Native Punx. Kim was reading, as was I, and I mentioned to her that I had contracted with the Wordcraft Circle people to host a Returning the Gift festival and I could use her help. I knew that she had been a vice-president of Wordcraft Circle in years past. We both knew the festival was going to be a tremendous amount of work. Something I did not know at the time was that she was scheduled to be on sabbatical. That was opportune, as organizing the festival would be impossible without her. After some preparations, we began work in September 2011.

Blaeser: To be perfectly honest, I had no desire to take this on. I’d planned a couple of regional Native lit conferences at UW–M in the past and knew what an enormous amount of work they are. This one is a national festival, it’s an anniversary event, and we have had only one year to accomplish what should really involve three years of planning. But the title Returning the Gift explains my involvement: The 1992 festival was a gift I received as a young writer; this one is my attempt to return the gift to the next generation of Native writers.

Stevens: That first Returning the Gift festival was started by Joseph Bruchac, Joy Harjo, and a few others. Joe’s influence on Native writing has been inestimable. In 1971 he founded (and still runs) the Greenfield Review Press, one of the major publishers of Native work, and for years he was the go-to guy for Native work. Both Joe and Joy are widely published—I don’t even know how many of their works are in print. A lot. Joy, too, is one of the most honored of Native writers, as well as being a jazz alto saxophonist.

Wordcraft Circle began after the original festival so that new people could join the group and carry forth the idea. Lee Francis Sr. was the original founder of Wordcraft Circle, but he passed away. Today his son, Lee Francis Jr., and Kimberly Roppolo of the University of Oklahoma are the principals of Wordcraft Circle. Lee and I are constantly talking, and the Circle provides ongoing support to the Milwaukee festival by getting its members involved.

Blaeser: The impact of that first Returning the Gift is simply beyond measure. I think those of us who were on hand for that first event will always hold it as an enchanted pocket of time. I was transformed by the realization that there were hundreds of Indigenous writers out there working in their own communities. Many of the friendships I made then have continued all these years. I got to know my wonderful colleague Professor Mike Wilson, whom I invited to apply at Milwaukee because I was impressed with several brief comments I heard him make at that first RTG. And it was there that I met another of our committee members, Cathy Caldwell, who teaches at MATC.

Simon Ortiz, Maurice Kenny, Geary and Barbara Hobson, and Joe and Carol Bruchac were among those who worked for almost ten years in bringing the first RTG festival to fruition. It was a massive undertaking. For the first few days, it was attended exclusively by Native writers; then for the last couple of days, other scholars and supporters of Native lit participated as well. I talked before about some of the practical things that have happened because of that RTG, but perhaps more significant are the relationships that developed out of it. The associations and collaborations that have arisen from that enchanted first event have affected not only those present but, through the process of affiliation, many of the current young writers who may have been toddlers when the first festival was held. The energy has continued.

What types of activities can we expect at the Milwaukee RTG festival beyond the usual panels and workshops?

Stevens: We’re going to have two rather famous Native writers there—Bruchac and Harjo. The first two days of the festival will be at the Hefter Conference Center and will include the usual panels, plenary sessions, and so forth. We’ll then move to the Indian Summer Festival grounds at Henry Maier Festival Park, where we’ll be taking part in education sessions, presentations, and storytelling for students until about 2:00 in the afternoon. Then we’ll shift to regular Indian Summer Festival programming, and Saturday and Sunday will include readings, dramatic presentations, and lots of storytelling. Attached to our tent will be Woodland Pattern’s tent for selling books—they have probably the best selection of Native American writing found anywhere.

Blaeser: Expect variety, including performances during the Indian Summer Festival at the lakefront that include a National Indigenous poetry slam, ten-minute plays for children, and poetry and jazz combos. I founded the Milwaukee Native American Literary Cooperative, which is comprised of Indian Community School, Woodland Pattern Book Center, Milwaukee Area Technical College, Marquette University, and UW–Milwaukee, as a way to pool resources, with everyone making a designated annual contribution, in order to be able to attract higher-profile writers and events to the Milwaukee area. The Cooperative was instrumental in bringing Joy Harjo, who will open the Indian Summer Music Awards, as well as the Bruchacs, who will do tag-team storytelling and perform as the Dawnland Singers. The festival program is still being assembled, but we already have some great public events planned.

What do you hope will be the long-term effects of hosting a RTG festival here in Wisconsin?

Stevens: Back in the 1990s, the Robert E. Gard Foundation put together a Wingspread Conference of Native American writers, which was fully paid for by the Gard Foundation—room, board, everything. It was great, and it really seemed at the time that something more would come of that conference. But, nothing really came from it.

I guess I would like to have the RTG festival lead to some kind of infrastructure for Native writers in Wisconsin. It doesn’t have to be as formal as the Wisconsin Fellowship of Poets or the Wisconsin Writers Association, but some kind of network of Native writers that keeps us from being isolated would be great. One of the things we are doing at RTG is getting younger writers involved. For instance, we hope to provide six $500 fellowships for young Native writers; we’ll hold a panel discussion with the Fellowship recipients and hear their perspectives on networking and other ways in which we can support what we call the Seventh Generation. It’s one of the most important messages we carry forth: Always prepare for the future.

Blaeser: Jim’s reference to the future hits the mark for me, too. We hope to foster the continuation of connections across tribes and organizations and to encourage collaboration among artists working in different media or genres. So the two words that focus the event for me might be celebration and legacy. Sometimes in all our striving—our struggles for survival, justice, dignity—we need the enchanted pocket of time I mentioned before. I hope that Native literary artists will come together and celebrate all they are and have done over the years, will revel in the camaraderie and enjoy one another’s talents. Then, invigorated, they can carry that energy forward to do more good work, become inspired to move in a new direction or emboldened to achieve something that previously seemed out of their reach. Already two regional publications have indicated to me that they would like to feature work from participants in a future volume.

Years ago, when I corresponded with the young Mi’kmaq writer, poet, and storyteller Lorne Simon, he wrote, “Poems draw memory like moon power pulls on the seas and creates tides.” This is what I hope the participants will experience at Returning the Gift this fall in Milwaukee: powerful memory, creating a tidal wave of creativity.