As an artist, a curator, a mentor, and a seeker, Nirmal Raja has made an indelible imprint on Milwaukee, where she has lived and worked for the last 24 years. Her humility, generosity, and the intellectual depth of her practice have enriched and inspired her many friends and collaborators across the arts community. Raja was born in India and lived in South Korea and Hong Kong before immigrating to Wisconsin, and her work consistently connects the intimate and personal with a consciously global concern. Her experimental, interdisciplinary practice often delves into difficult emotional realms. Investigating personal, social, and political conflicts, Raja seamlessly melds complex content with intriguing surfaces and materials to create beautiful and engaging works.

Nirmal Raja’s solo exhibition, Asking Questions of a Thread, was guest curated for the James Watrous Gallery by Ann Sinfield. We are honored to work with Ann, whose probing and insightful approach to Raja’s work has resulted in a powerful gallery presentation. Asking Questions of a Thread was on view through October 20, 2024.

Jody Clowes: The title of your exhibition, Asking Questions of a Thread, is beautifully open-ended. How would you describe what that phrase means to you?

Nirmal Raja: This is related to the title of the video and poem in the exhibition, “Can I ask a question of a thread?” It seems to fit and connect with everything in this show. Questioning is inherent to my practice because it’s very inquiry based. It’s always about learning more, either through the practice itself or trying to understand what’s going on around me, so it needed to be evocative of that kind of a searching process. The word thread itself could refer to inquiry, metaphorically, because we think of trains of thought as threads of investigation or threads of thinking. That was the other part that seemed to fit in.

J: That makes sense. Curiosity and questioning are so central to everything that you’re doing. I just love the way that thread, as you say, is an elusive term that can lead in lots of different directions.

While you work across many media, fabric, thread, and clothing have been really central to your practice. In many cases, these textiles are freighted with cultural or personal meaning. I’d love to hear more about how the stories embedded in these kinds of textiles inspire you, or lead you to work with them in a particular way.

N: Well, since I grew up in a culture that has such a rich textile history, fabric is almost the first language that I learned. I grew up learning embroidery from my grandmother, crochet from my grandmother, and just absorbing this love for fabric. My mom used to design clothing for me and did a lot of negotiating with the local tailor to have certain clothes made. So, there’s this real passion for fabrics and the beauty that they hold. But as I get older, I think it’s also just that fabric is so intimate, so connected to the body. I almost think of it as a second skin. Used fabric, especially, is important for me because there is this belief in India that when somebody has passed, only the most important, expensive clothes that you’d really want to save would be given to family members. The rest of the clothes would be burned because a lot of cultures in Asia believe that the essence of the person gets absorbed by the clothing they wear. Used fabrics kind of take on their owner’s personality, or their DNA becomes embedded within the fibers. I can’t tell you how this belief emerged; it could be related to a concern about contamination...that’s probably how it originated. But this connection between fabric and body is very important for me because I think when I use these fabrics in my work it’s also about harnessing that essence.

Whenever I work with fabric, it becomes more about the meanings that it holds rather than the techniques I employ. I’m really translating that fabric into a different way of experiencing it.

J: So, for example, for your piece Entangled, you were working with saris collected from women you had met, but didn’t necessarily have a personal relationship with. In contrast, you’ve made a series of pieces with the clothing your father left behind after his death. How is it different to work with fabrics from acquaintances versus someone close to you?

N: I think that with Entangled, using the saris was more about the aesthetics of all that color and the importance of sourcing the saris from the community. When I created this over a decade ago, the work was more about the dichotomy of the beauty and richness of the culture that I come from, and my complicated relationship with that culture. Once you leave the place you grew up in and are negotiating the two cultural geographies, you’re trying to choose what’s best from each culture or trying to examine the culture that you come from with a removed perspective and with a little more critical eye. I think migration allows you to look back at your own culture to see what other people see in your culture, too. There’s so much complexity as a South Asian woman, or any immigrant woman living in the U.S., that you’re contending with. I wanted to capture that complexity and the ‘tangle’ as a metaphor was important because I feel like I’m always trying to untangle puzzles and problems in my life.

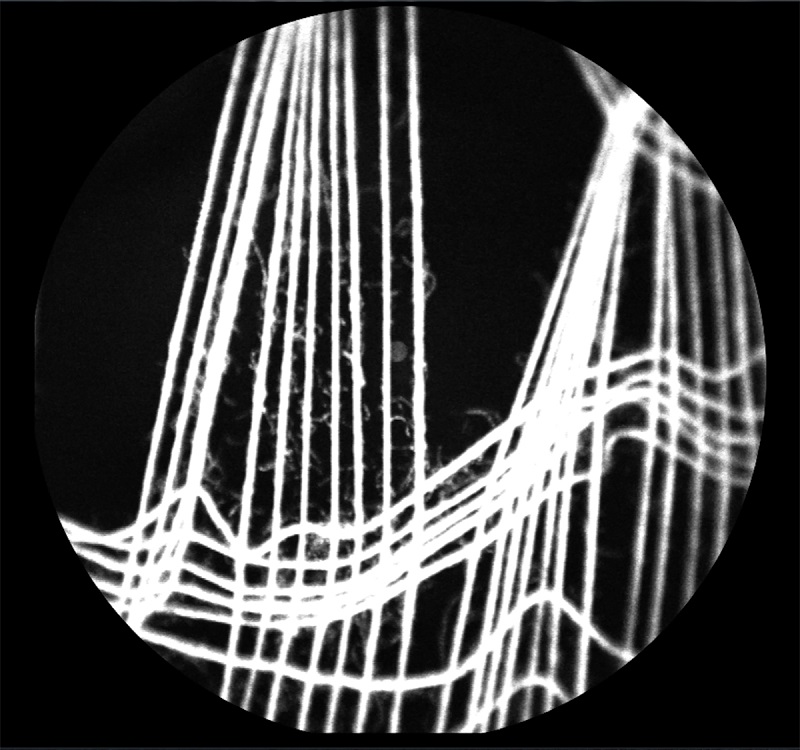

And yeah, I think it’s very different working with my dad’s clothes. It was very much about tapping into a feeling that he is still with me, as his DNA is in me. His memories and his influences are very much part of my personality; I’m very much like my dad, actually. He’s with me in that way, but also the sudden disappearance of his physical self was very shocking. I’ve lost my grandparents, but I’ve never really lost somebody that close to me before. It’s almost like a mirror of myself passing away. I wanted to try and express that sense of his ‘being there’ and ‘not being there’ at the same time, rather than aesthetics, color, or anything like that. It was about taking that fabric, making an impression of it, and letting the fabric itself burn away, which is what happens with the burnout technique [dipping the fabric in porcelain slip and firing it in a kiln]. In the finished piece, there’s this hollowness. If you were to cut the sculpture open, you would see the little pores or spaces where the fabric was burnt away in the kiln. I feel like that helped me understand the conflicting feelings I have; to reconcile this feeling that he’s here with me, but he’s also gone and I can never really touch him.

J: I think it’s a beautiful metaphor. I really love the way the piece holds that impression of the fabric, but the substance is no longer there.

N: And also, cremation is how I got the idea because in my culture, we cremate the dead. Usually, the funerary rituals are only done by the son; the women do not go to the cremation grounds or anything. But I insisted on going with my brother. The experience is not as clinical as what people do here. You know, when you go to a funeral here, it’s an embalmed body in a casket or a closed casket, right? Everything that I experienced during my dad’s funeral was very visceral, very direct. It’s impossible to ignore the ugliness of it, but also there’s so much beauty in the ritual itself. I was a little shocked that I was actually noticing beauty when I was so sad.

J: Thank you for sharing that. Being so directly confronted with the reality of our bodies’ mortality must give you a real sense of closure, even if it’s incredibly difficult.

I want to go back to Entangled, in which these fat tubes sewn from saris become an unwieldy, snaky mass, and also reference your Contained series, in which saris are embedded in plaster and yet spill out, breaking the silhouette of the mold. There’s an element of chaos in these works; a sense of repressed energies that could shift unexpectedly. If these works made with saris are a reflection on the experience of immigrant women in that context, how would you describe that sense of coiled or latent energy?

N: I think that throughout my life I’ve resisted being put in boxes because I grew up in a very conservative, traditional home and there were certain expectations of young girls and women. I found it very suffocating and restrictive. When I came to this country, I felt like I was being put in a box again, with certain expectations of what my art should look like—that exoticism or objectifying gaze. Even with my interdisciplinary practice, I felt the art world was expecting me to make similar work with the same medium, like, “Why are you switching gears now?” Or galleries expect you to do things a certain way. I’m always trying not to fit into anybody else’s idea of who I should be. In the Contained series, breaking out of those cubes comes from that urge to make sure I’m resisting that kind of definition.

J: Two of the pieces in this exhibition—Weight of our Past and What is Recorded, What is Remembered—document performances you’ve done. How do you feel about that translation when a performance piece is represented in a gallery space through photographs or video? Has that translation ever changed your understanding of the work, or revealed something that might not have been foregrounded in the performance itself?

N: Just like I try to find a material language that accurately expresses what I want to say, performance becomes one of those tools. I’m very aware that my performance is for the camera. I don’t think of it as documentation as such; I think of it as an inherent artwork where I’m using the lens to get to that expression. I do not perform live. I usually work with someone like Lois Bielefeld or Maeve Jackson to either collaborate with me or document the work with video or photography.

With these two bodies of work, there is one important difference. What is Recorded, What is Remembered is very much a collaboration that Lois and I came to together. We were walking down the Riverwalk in Milwaukee [where there is an engraved timeline of Wisconsin and American history] and thinking about history right after Trump was elected. The work emerged out of that collaborative brainstorming with Lois. But for the Weight of our Past, I commissioned her to make photographs [of Raja engaging physically with her sculpture Entangled] with the primary purpose of expressing how the meaning of that piece had changed for me. A decade after making it, it became very much about carrying a cultural burden; how I wanted to almost discard it, and yet it’s just part of me that I’m dragging along wherever I go. Since I had worked with Lois earlier, I felt comfortable and I am grateful that she agreed to document these performative actions for me.

J: I didn’t realize that Entangled existed for so long before you felt you needed to perform something with it. Has that ever happened with other pieces, where an object calls out to be shared through performance, rather than the idea of the performance coming first?

N: I have a daily studio practice, and I was making a series of bricks, experimenting with pouring fabric and plaster together into brick-shaped molds just to see how those two materials reacted together. But then I started making more and more, one every day, and eventually they found their place into a sculpture/ video performance called The Wall Within. It was made right after the Black Lives Matter movement emerged, and I wanted to make a work that spoke about witnessing social change, and all the different protests that were happening, and the sense that the power structure was changing at that time. Maeve Jackson came to my studio and filmed and edited the work with my direction.

J: I’m so impressed by the discipline and focus of your studio practice. You put your art education on hold until your kids were grown. But since then, you’ve been fiercely dedicated to your studio practice and curatorial work. You must have had creative outlets before you could commit to making art full time. When you were young, did you have a sense that art would become so central to your life?

N: I always wanted to be an artist, even as a child. But I grew up in a conservative home and going away for college was not an option. I did my undergraduate degree in English literature so I could stay with my parents and go to college from home. But when I came to this country, I did my first year at MIAD [Milwaukee Institute of Art & Design] in 1991 and it was amazing. I totally wanted to continue, but then life changed. We had to move for my husband’s training, and we had two children. The one way I could keep in touch with art was actually taking classes. So I took classes at Moore College of Art, and Maryland Institute College of Art. I would always take one credit course at a time, and was able to fit in childrearing and my husband’s schedule. That’s how I kept in touch. By the time we moved back to Milwaukee and I finished my MFA, 16 years had passed. But I sustained my interest in art through taking classes.

J: When you were a child in India, what was your image of an artist’s life? Did you have models around you that inspired you?

N: I was very good at drawing and painting. Being an artist meant being a painter. Little did I know that art was always around me, whether it was making a flower garland for morning worship, or sewing and mending garments. Those kinds of things were happening around me and were part of my life. At that time, of course, the formal idea of what an artist “is” was what I wanted to be. But I’ve moved away from the traditional way of making art, especially oil painting. I used to make a lot of oil paintings and I don’t do that anymore, specifically because of its very Eurocentric and colonial history. It just didn’t seem authentic to my own story.

J: I think it’s fascinating how you have circled back to these traditional forms, but are using them in such a personal, contemporary way.

You’ve been closely engaged with Milwaukee’s art community for many years, collaborating with other artists, curating exhibitions that showcase local artists and bring the work of international artists to the city, and serving as a mentor through the Milwaukee Artists Resource Network. Can you describe what it’s like to be part of a community like Milwaukee and how the support of other artists has been important to your development?

N: I think as an interdisciplinary artist, it’s almost impossible not to seek help because you’re this jack-of-all- trades, master of none. I’m always in a space where I’m wanting to learn more about a certain technique or material because it’s the perfect language for what I want to say. I’m always reaching out to people to show me how to do things, or taking a class, or doing a video tutorial, or collaborating. There are many, many different ways of connecting with people to find out how to make what I want to make. That’s just part of the production of my artwork. But I think it also speaks to a strong belief that we are all interconnected and you cannot make art in isolation. Influences come from all around you and the people that live around you shape you in some way. I do not believe in art in isolation. I feel like we are always changing and being influenced by the surroundings.

Milwaukee has been hugely transformative for my career because, although we have so little funding from the state, our wealth is in the people. I’ve found generous people —willing to help support or assist by sharing their knowledge and expertise. So grateful for that! When I mentor emerging artists and curate exhibitions—to give voice to people who don’t get seen or have the space to express themselves, it is my way of giving back. I think that supportive, reciprocal spirit really exists in Milwaukee. It was hard to say goodbye to that. Milwaukee feels like it is just the right size for that kind of thing to happen.

J: In a larger city like Chicago, there are obviously networks of support, but it’s impossible to know about everything that’s going on. Milwaukee, for better or worse, is a place where you really can get a sense of the city’s art scene as a whole pretty quickly.

N: As far as curating is concerned, during my travels back and forth to India and travels with my husband, we always make it a point to visit the museums and galleries wherever we go. I had this urge to bring some of what we saw and share it with Milwaukee. So curating art is important to me because I’m forming networks and connections in the process. For example, work made by artists in India was shown at the Union Gallery [at UW–Milwaukee]. Those artists eventually hosted some artists from Milwaukee for an exhibition in India. That kind of cross-pollination of artwork and ideas is something that’s very inspiring to me because when you see art from a different place, you begin to understand the people that made that artwork. I like to facilitate that whenever I can. That’s how my curating started. The other goal was to widen the visual culture because it’s very easy in a city like Milwaukee to keep seeing work by the same artists. I thought that to expand what you can see would be really exciting.

J: I think your curatorial projects have been a real gift to the community. As a curator and as an artist, I know you are very sensitive to how the arrangement of an exhibition affects the visitors’ experience, and you’ve typically been closely involved in the presentation of your own work. What has it been like to have Ann Sinfield, Curatorial Lead at the Harley-Davidson Museum, curating your solo exhibition for the Watrous Gallery? Have you been surprised by any of the selections she has made or the questions she’s asked?

N: I was very excited about this exhibition because you get so involved in your practice that you don’t often get an insight into what other people see in it. I almost want to be there as a fly on the wall to see what other people say about the work or how they interact with the work—which way they walk or what catches their eye first. I want that removed perspective, especially because working with so many different media gets me lost in a maze sometimes. To have someone decode and connect the dots is illuminating for me, so I’m eager to see what happens in the space itself. I trust Ann and I’m curious to walk through the exhibition as if it was not my own work.

J: I’m also curious to see your response, because it is an act of trust to hand it over in that way. And speaking of an act of trust, you’re still creating some of the pieces that will be in the exhibition—the Accretions series of fabric pieces. I think it’s wonderful that Ann was open to including things that are still in process in the exhibition. Tell me about how those pieces have evolved.

N: Ann did see the first layer of the Accretions series, so she could have a sense about what they would look like. I think the move [to Massachusetts] was a very big part of that work because I began to discover little things I have held onto over the years that eventually found their way into those pieces. Those works are very much about attachment to material things for sentimental reasons or because things are gifted to you. I ask myself “why I hold on to this particular bead that was part of a garment I wore as a 12-year-old?” for example —things that just linger with you. Initially, the titles of the pieces were Fly Papers because they are passive surfaces—where things just accidentally end up on.. I discovered things in nooks and crannies when the furniture got moved. All kinds of things have been going onto these surfaces. The challenge is trying to keep it aesthetically pleasing. I’m trying to pause the work at a place where I think it’s okay to be viewed in a professional setting, but I’m imagining these pieces as durational works that would only end when I pass. They would just gradually get more unwieldy, heavy, and layered.

J: I love the idea that we’re seeing these works in the gallery at a certain point in time, but they’ll never be the same again. Maybe this will become a documentation project for you along the way.

How did Ann approach you to curate the exhibition?

N: Ann has been following my work for almost a decade now. She usually comes to my exhibitions, and she has written about my work for her blog. I did an exhibition during the pandemic called Feeble Barriers, including embroidered masks with quotes from health care workers, and she wrote a beautiful essay about that exhibition. We eventually started conversing, and she came for studio visits and wanted to submit something to the Watrous open call.

J: It’s exciting to work with the two of you. We have worked with guest curators a few times in the past, but your show is the first guest-curated exhibition to come out of our recent call for artists process.

I wanted to end with two questions from our intern Suchita Hothur, who is a very thoughtful young woman. She’s from Bangalore, and she suggested two questions connected to your cross-cultural experience that would never have occurred to me. The first one is about the cast iron braids you made during your Arts/Industry residency at Kohler Company. In India, hair and braiding hold an important cultural significance. How are cultural expectations and values reinforced through unspoken rules, as here, with hair? Can such practices simultaneously hold beauty and pain?

N: Yes, it’s very connected to the work that I’m making. I’m actually thinking about the braid being a form of patriarchal control. When I was growing up, I was not allowed to cut my hair because the ideal form of feminine beauty is to wear long, oiled and braided hair. It wasn’t until I came to this country that I cut my hair almost as an act of rebellion. At the same time, I was noticing that the lives of my aunt, my mom, and my grandmothers in the traditional setting are viewed as weak or dismissed to the domestic realm. But women in the domestic realm in cultures like these also wield a lot of power. There is a certain kind of strength, or forbearance, that I witness in my own family and a lot of Indian American women around me. I wanted to kind of reverse that patriarchal understanding of the braid by using a material such as iron, which is an extremely heavy material—considered strong, but actually it’s not, it’s brittle. It’s about how strength and grace can be combined as I witness them in women in my family- who did follow all of these traditional norms and lived their whole lives in this patriarchal framework but at the same time were strong and had gravitas. So that’s what I was trying to explore.

J: Suchita also suggested that the patterns in some of your work reminded her of rangolis. Is that something that seems true to you?

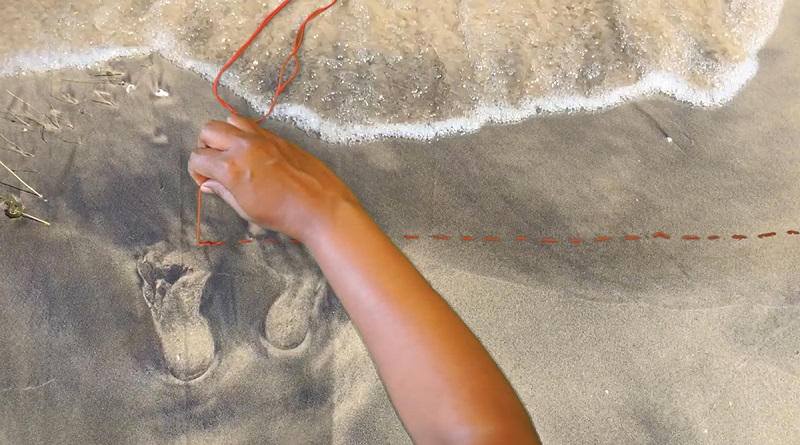

N: Yes, I have made previous work using rangoli powder. Every morning [in most households in India] women wash the threshold and then make beautiful patterns with powder—either rice flour or a chalk grit. I love this act because it’s about creating everyday beauty, but also the work gets worn out, blown away, or walked over in just a few hours—not even a few, just an hour or so. I’m very drawn to the transience, the disappearance of that labor, and the momentary beauty that you’re walking over. Also, I love this determination to make your surroundings beautiful and to honor that doorway, which kind of defines the insider and the outsider. When you create a path—a design in front of the house—the meaning is to welcome your guest. You are giving whoever is passing through that threshold something beautiful to look at and welcoming them into your home. So, I did make two works, five feet by five feet on black canvas placed a few inches of the floor horizontally, where I used the chalk grit that’s used in rangoli, but not using traditional patterns, but DNA patterns. One work depicts mitochondrial DNA, the particular kind of DNA that gets transferred from mother to girl child. I wanted to make that because rangoli is practiced only by women and I wanted to speak about lineage that’s passed on through ritual and through these practices. The other is just a DNA strand. It’s loose powder and at the end of the exhibition it just gets shaken out.

J: That’s beautiful. It’s kind of a perfect metaphor for an exhibition as well. You’re creating this beauty, welcoming people in to experience it and it’s very personal, almost like inviting somebody into your home. But temporary—exhibitions are so ephemeral.

Thank you so much. I greatly appreciate your candor and your thoughtfulness.

Note to the reader: Images of almost all of Rajal’s earlier work can be viewed at nirmalraja.net, including those pieces made with chalk grit, which are titled The Never Ending Line.