Across the country, Tribes have become key voices in discussions and initiatives related to climate change and sustainability. Wisconsin is home to several leaders in this growing movement, including Sara Smith, who has emerged as not only a bridge between Tribal partners, but also as a crucial catalyst for bringing more attention, resources, and urgency to the challenge of building climate resilience across the Midwest.

As the Midwest Tribal Climate Resilience liaison at the College of Menominee Nation’s Sustainable Development Institute, Smith helps Tribal Nations partners access research and expertise at the Climate Adaptation Science Centers. Smith has become a go-to source on culturally informed climate science for a wide range of coalitions, organizations, university partners, and government entities.

Smith’s role is to incorporate Indigenous Knowledges into sustainability and climate adaptation efforts in the region, and her work is deeply informed by her Oneida heritage. “My family jokes that they had to keep an extra pair of shoes in the car when I was a kid because I was always running around barefoot,” she says of her upbringing in Appleton. Her Nana was the first to inspire her to explore the natural world, and Smith recalls bringing home “smelly” collections from the Door County beaches her family visited regularly.

“We were always camping, up in Door County or down at Devil’s Lake,” Smith says. “I have always had a profound love for the outdoors.”

That early interest in the natural sciences rekindled into a passion during her college years at the University of Wisconsin–Green Bay, where Smith pursued a dual degree in biology and First Nation Studies. Though Smith’s interdisciplinary focus puzzled her friends at the time, she sensed early on that the connection between these fields was significant.

As graduation neared, advisors encouraged Smith to apply for a fellowship at the State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry (SUNY-ESF). The program’s faculty included Dr. Robin Wall Kimmerer, the botanist-turned-author whose bestselling Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants was published the same year Smith was accepted to her fellowship. The book, which to date has sold more than 2 million copies, is a unique compilation of personal memoir, Western plant science, and Indigenous Knowledge rooted in Kimmerer’s Potawatomi upbringing.

Like Smith, Kimmerer forged her own path as a scientist whose work is grounded in Indigenous Knowledge. Also like Smith, Kimmerer has a close connection to Wisconsin: she completed her advanced degrees at the University of Wisconsin–Madison in the early 1980s, and it was during her time as the caretaker of the UW Arboretum that Kimmerer first realized she wanted to build a career that braided Western and Indigenous understandings of the living world, a perspective she terms “two-eyed seeing.”

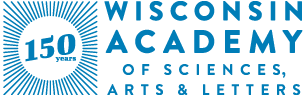

“I had no idea who [Kimmerer] was when I applied, but I called her, we had a good chat, and she said, ‘you’re coming here,’” Smith says. She began her fellowship at SUNY-ESF that fall. Under Kimmerer’s guidance, Smith conducted research on the sustainably managed forests of the Menominee Nation in Wisconsin, and her thesis incorporated traditional Menominee knowledge into her studies on ectomycorrhizal succession (the relationship between fungi and plant root systems) in White Pine stands on the Menominee Reservation.

“One of the protocols from the elders was that they have reverence for the underground community in the forest, so they don’t want to disturb them,” Smith says. “Out of respect, I only looked at things that were fruiting above the ground.

Smith quickly evolved from student to teacher during the project, and she led a team of interns into the Menominee forest to show them techniques for designating plots, finding mushrooms, collecting and identifying samples, and dehydrating them for her research. Their days began before dawn to maximize work before the day’s heat and often stretched into late evenings. Crawling through pine duff, covered in tick and mosquito repellant, they photographed each find in situ before processing it.

After completing her ecology program, Smith quickly found a position as a natural resource technician with the Stockbridge-Munsee Community Band of Mohican Indians in northeastern Wisconsin. She began to focus more specifically on climate science, which eventually led to her transition to the climate liaison position at the College of the Menominee Nation in 2017. She serves all thirty-five federally recognized Tribal Nations in the Midwest region, including eleven federally recognized tribes in what is now known as Wisconsin.

Smith now helps to document and articulate how the impacts of climate change are directly affecting Tribes in Wisconsin and across the Midwest. For example, rising winter temperatures have substantially decreased frost, snow pack, and ice cover on the Great Lakes as compared to past decades. Various fish and mammal species are facing pressure as a result, and the changing water systems are also prone to larger and more frequent floods that strain roads, bridges, and other infrastructure not designed for these events. Yet Tribes are typically reservation-bound, meaning Indigenous communities can’t simply migrate elsewhere along with their plant and animal relatives.

One of Smith’s first assignments as climate liaison was to help develop Dibaginjigaadeg Anishinaabe Ezhitwaad: A Tribal Climate Adaptation Menu (TAM), a project under the aegis of the Northern Institute of Applied Climate Science (NIACS). The first of its kind and regional in scope, the TAM was published in 2019 with funds from the Great Lakes Indian Fish & Wildlife Commission, and a collaborative team of authors represented Tribal, academic, inter-Tribal, and governmental organizations across Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan.“Working on that project helped me learn what was going on already—which was not a lot when it came to incorporating Indigenous Knowledges into Western science, or into planning or tools,” says Smith. “I was grateful to be part of that team because, without that, I wouldn’t be as good of a liaison as I am right now.”

In 2019, the federal government doubled funding for regional climate adaptation science centers, and a new Midwest-specific center was established. By 2021, Smith’s work had expanded substantially, and in 2022, she received an award from the Minnesota Climate Adaptation Partnership in recognition of her growing contributions to climate adaptation planning across the Midwest. Smith’s influence in the field is especially evident in the latest edition of the National Climate Assessment, a comprehensive report produced by the U.S. Global Change Research Program that assesses the impacts of climate change on the United States. Smith co-authored the chapter covering the Midwest. “[Smith] worked very hard to make sure that in that Midwest chapter, Indigenous worldviews and language were incorporated throughout,” says Allison Scott, Deputy Midwest Tribal Liaison at the College of Menominee Nation. This included shifting language in the text of the report to refer to entities in nature as relatives or living beings, rather than describing them as “resources.”

Smith, with her colleague Scott, are also tasked with creating in-person forums for information exchange, and they regularly produce workshops for Tribal partners to help them better understand, communicate, and meet the needs of Tribes. Bringing diverse stakeholders together to discuss contentious topics related to climate change can be challenging, but Smith has developed a reputation for creating effective and informative sessions.

“I admire her willingness to share her knowledge and expertise with others, so that they can also do a good job of recognizing, honoring and engaging with different ways of knowing, in the work we do in climate adaptation,” says Olivia LeDee, the deputy director of the Northeast Climate Adaptation Science Center.

“[Smith] has a high level of emotional intelligence that’s a huge asset on work that depends on relationships and reciprocity,” says Scott.

As 2024 draws to a close, Smith and her colleagues are most focused on continuing to build Tribal capacity to implement and manage their own climate-adaptation projects, which has become more possible in recent years due to increased financial support from agencies including the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the Environmental Protection Agency. “The additional funding increases Tribal staff’s ability to engage with what we offer and implement what we suggest,” says Scott.

One of Smith’s main areas of focus is the Shifting Season Summit. Held in October, the summit is a multi-day meeting that brings together Tribal communities, scientists, and other stakeholders to share knowledge and resources to benefit climate change adaptation efforts. Participants engage in hands-on workshops, field trips, and interactive sessions, and Smith’s agenda also includes interactive components to help participants connect personally to the outdoors. For example, they prepare and eat Indigenous foods and go on a field trip to gather corn and make art with the husks they bring back.

Smith is also beginning to expand her work internationally. With support from the Waverley Street Foundation, Smith is actively building relationships with Indigenous communities in New Zealand, Norway, and Finland. In March, Smith traveled to New Zealand for a knowledge exchange with Indigenous Maori people to talk about the impacts of climate change on sustainable forestry practices. To solidify the new partnership, Smith received a traditional Maori tattoo on her forearm.

“The work of adaptation is not just about the environment—it’s also about health, about land and sovereignty, it’s about our institutions,” Smith says. “Technology, economics, and human behaviors are all part of it. Thinking about this as a whole and how we go forward is really important.”