The behind-the-scenes team of curators at the Richter Museum of Natural History in Green Bay serve as keepers of fundamental knowledge about the diversity of life on Earth in order to educate and inspire scientists, artists, and students.

When most of us visualize a natural history museum, we imagine towering dinosaur skeletons and the skins of large mammals mounted in ferocious poses standing in massive exhibit halls. What we don’t picture, because most of the general public never see them, are the hundreds of thousands (even millions) of scientific specimens stored and studied behind closed doors. In fact, some natural history museums have no space at all to exhibit their collection, and function entirely as research facilities.

With the exception of a few display cases throughout Mary Ann Cofrin Hall, the Richter Museum of Natural History at the University of Wisconsin–Green Bay, founded 50 years ago, is one of these museums. As a result, the museum’s significant contributions to the university and the greater community were not always obvious.

In 2018, a portion of my faculty position as Associate Professor of Human Biology was reassigned so I could replace the museum’s retiring full-time curator. Since then, we have strengthened and forged new connections and collaborations to promote the important work at the Richter, and natural history museums in general. We’re working to expand its reach to a wider and more diverse audience, and increase its impact on research, education, and scientific advancement.

The Richter Museum is housed in a purpose-built facility in Mary Ann Cofrin Hall, in the heart of the picturesque UW–Green Bay campus, and is part of the Cofrin Center for Biodiversity. The center, a program of the College of Science, Engineering, and Technology, manages the museum and its plant counterpart, the Fewless Herbarium, as well as six natural areas in northeastern Wisconsin.

The Richter Museum was established in the 1970s thanks to a generous donation by the late Carl Richter, a native of Oconto, Wisconsin. One of the state’s most prominent ornithologists, Richter spent a great deal of his life assembling a remarkable personal collection of animal and archaeological specimens. Most of his specimens were collected in the western Great Lakes region, though he also obtained specimens from around the world, including Canada, Mexico, Central and South Americas, and Europe.

The museum’s website gives a great overview of Richter’s gift and the museum’s significance:

“Richter’s 1974 donation included over 10,000 sets of bird eggs, and the museum now houses over 11,000 sets, making it one of the largest egg collections in North America. The museum also contains tens of thousands of animal specimens, mostly in the form of study skins, skeletons, and alcohol-preserved specimens, and representing all major branches on the tree of life. With a focus on the Great Lakes fauna, all bird species that breed in the area are represented, as well as most of the fish, mammal, reptile, and amphibian species that call the great lakes area home. The collection of non-vertebrate animals is notable for containing significant numbers of local insect, mollusk, and spider species.”

Significant among Richter’s collection is a mounted male Passenger Pigeon, a species that famously was driven to extinction by commercial hunting for food in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The last living individual died in captivity in 1914, and the adult male specimen at UW–Green Bay is one of only about 1,200 birds (either mounted or stuffed as study skins) in existence, worldwide. Even more noteworthy, Richter’s egg collection includes five specimens from the extinct bird, and we now know these specimens contain DNA from the embryos collected long before anyone knew what DNA is or why it’s so important to our understanding of all living things.

Since Richter’s donation, the museum’s collection has continued to grow, and now forms one of the most significant collections in the state. Most of the animals that end up in the collection today were killed in collisions with windows (birds) or cars (birds and other vertebrates), and the museum has federal and state salvage permits to possess these specimens.

A Resource for Scientists and Artists, a Training Ground for Students

Natural history museums are the keepers of our most basic information about the diversity of life on earth, serving as unique and invaluable storehouses of information, as well as the source of valuable new knowledge. Studying preserved specimens and the crucial data that is archived with them informs much of what we know about the diet, behavior, and ecology of living animals. Biologists who work with understudied groups like insects, and even better-known species such as frogs, are often overwhelmed by the number of species that have yet to be formally described and named. Untold new species sit in museum collections for years, awaiting a scientist with the right expertise and time to do the tedious work needed to assign them a Latin name. For example, in 1996, while I was a graduate student at the University of Kansas Natural History Museum, I described an unnamed species of frog based on specimens that had already been in their collection for more than 20 years.

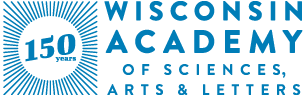

While we can only guess at the future scientific value of such collections, the Richter Museum is engaging students and the community at all levels. In the summer of 2023, members of the university’s Lifelong Learning Institute, which offers a plethora of discovery and engagement opportunities through noncredit classes and experiences to area residents, spent two days drawing from specimens in the museum under the tutelage of a professor emerita of art. Last summer, several groups of 4th through 8th graders toured the museum to learn about “magical creatures” as part of the Wizard Academy, a two-day camp led by Humanities Associate Professor Valerie Murrenus Pilmaier. A growing number of youth camps that incorporate the museum’s collections are conducted every year.

Being part of a university campus, the museum sees the most utilization from UW–Green Bay students and faculty. The courses most obviously suited to use the collection are taxon-based and related to biological classification, such as entomology (insects) ornithology (birds), mammalogy (mammals) and ichthyology (fish). Classes in wetland ecology and marine biology also rely on the museum. Viewing specimens up close helps students learn the subtle differences between species, as well as the confounding variation within species, and thus become much more skilled at identification in the field. Our graduates have put these skills to use at government agencies such as the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources and non-governmental organizations like the Nature Conservancy. Those students often to collaborate with UW–Green Bay faculty, and in many cases continue to contribute specimens to the museum to document that work. In the last six years, the Richter Museum has hosted interns conducting projects in public education, collection curation, and database management, who then moved on to work in positions in outreach at the Green Bay Botanical Garden, and as archive Assistant at the Wisconsin Historical Society, and fish Biologist for the U.S. Forest Service.

Biology and environmental science students at UW–Green Bay are not the only students to benefit from the museum’s presence. For decades, art students in classes such as Two-dimensional Design, Three-dimensional Design, Introductory Drawing, and Intermediate Drawing have made studies of specimens housed in the Richter. The museum is even featured on the drawing program’s main webpage. And because part of the egg collection is available as photographs in our online database, students and instructors at other institutions regularly make use of this rich resource.

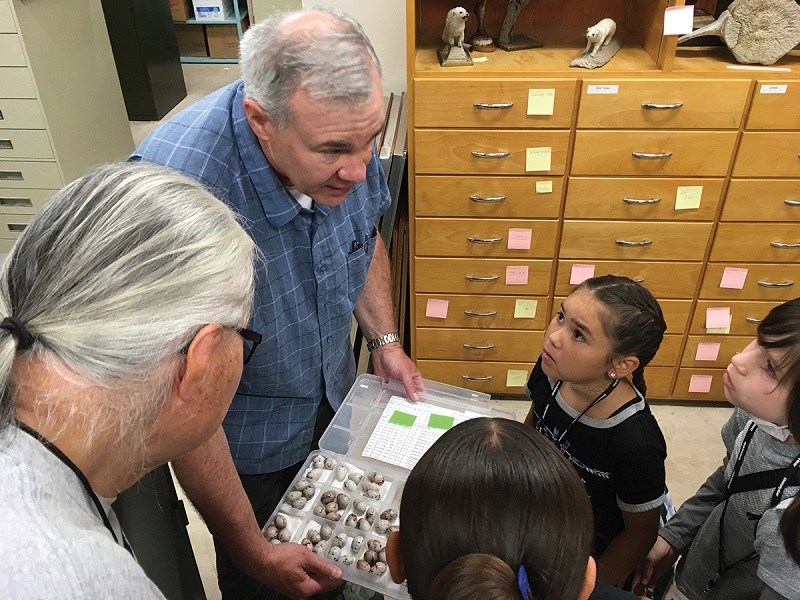

In 2021, students approached me about starting a Scientific Illustration Student Organization, and once established they hit the ground running. From the start, the meetings were very well attended, and the group began participating in a variety of campus events such as the STEM Family Day and Biodiversity Day. When we approached the UW–Green Bay Teaching Press about publishing a coloring book based on students’ illustrations, the project grew into Wandering Toft Point, a nature journal featuring completed illustrations and poems inspired by one of the natural areas managed by the Cofrin Center for Biodiversity. Understandably, many of the illustrators who contributed to the book relied on Richter specimens to hone their skills and accurately represent the species depicted. As the organization’s advisor, I use the collection extensively to help students learn illustration techniques and understand why scientific illustration is still an important means of studying biodiversity.

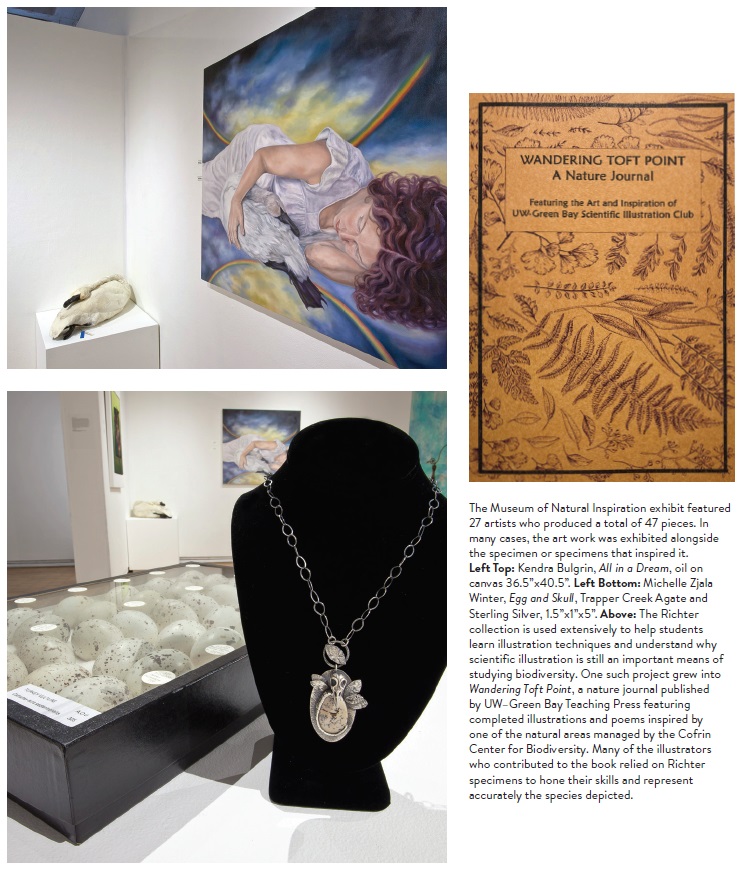

As part of our efforts to promote the museum by creating more diverse opportunities for community engagement, we launched one of our most ambitious and successful projects in 2018, when the university’s Lawton Gallery of Art hosted a group show called Museum of Natural Inspiration: Artists Explore the Richter Collection. The idea came to me when I was asked to join the curatorial advisory committee for the Lawton Gallery at roughly the same time I was appointed Richter curator. Working with now-former Lawton Curator Emma Hitzman, we conducted an open call for interested artists. Over the course of the next year, I hosted approximately 50 artists from as far away as Los Angeles on tours of the Richter, and tasked them with using the collection as inspiration for new work. Ultimately, 27 artists produced a total of 47 pieces that were included in the show, and in many cases the work was exhibited alongside the specimen or specimens that inspired it. Besides being immensely popular, the show forged connections to the museum throughout northeast Wisconsin and beyond. One of the participating artists has since opened a gallery in De Pere, and in 2022 hosted an exhibit featuring Richter specimens alongside nature-inspired art.

We are extremely fortunate that UW–Green Bay has made our biological collections a serious priority, as this is not always the case at other universities. Natural history collections can be viewed, even by scientists, as antiquated institutions with little to contribute to modern biology. As a result, such collections are often neglected, especially when resources are in short supply. These cases are tragic, because biological collections are not just irreplaceable, they are at the core of our understanding of biodiversity. Students at UW–Green Bay are enriched by the collection in so many different ways, from a variety of different classes in biology and art to regular research opportunities for undergraduates and graduate students funded through the Cofrin Center for Biodiversity. I relish every opportunity to share the collection with the university community and visitors alike, making the case for why we need natural history museums. Anyone with even a modest interest in nature will come away impressed by the depth and breadth of our collection and its distinctive ability to teach, engage, and inspire.

To learn more about the museum or visit the collection for research or educational purposes, contact Dr. Daniel Meinhardt, Richter Museum Curator, at (920) 465-2398 or meinhada@uwgb.edu.

All About Access

Fascinated by the workings of archives and museum collections, and knowing the goal was for these collections to be accessible, I took an internship at the Richter Museum as a graduate student in Library and Information Studies at UW–Green Bay. My job that academic school year was to standardize the existing digital catalog and upgrade it to a permanent collection management system. This included confirming the spellings of the names of the donors, as well as the items’ scientific names, and creating a controlled vocabulary list (such as “dead on road” instead of “roadkill”).

None of this was easy, but it pushed me to make the catalog simple and straightforward for all users—and set a course for my career goals and ambitions. I am currently working with the metadata remediation team at the Wisconsin Historical Society to prepare for their own migration to a new management system for their digitized collections. Creating access to archival materials and museum collections is my passion, and I appreciate the ability to apply my knowledge and experiences from the Richter Museum, as well as other opportunities, to make this possible for students, scientists, citizens, and more.

Beth Siltala, Archives Assistant, Wisconsin Historical Society

SPECIES 101

"The beginning of wisdom is to call things by their proper name," Confucius wrote. Yet determining that proper name is not always quite so easy. Perhaps we know which animal to conjure when we say the name mountain lion, but how about when we say panther, cougar, or puma? All of these terms are used interchangeably to name the species that scientists formally describe as the Latinized, two-part name Puma concolor. A system like this is crucial to avoid the confusion that can arise from the many different names, in some cases from multiple languages, which are used to refer to a single species.

"The beginning of wisdom is to call things by their proper name," Confucius wrote. Yet determining that proper name is not always quite so easy. Perhaps we know which animal to conjure when we say the name mountain lion, but how about when we say panther, cougar, or puma? All of these terms are used interchangeably to name the species that scientists formally describe as the Latinized, two-part name Puma concolor. A system like this is crucial to avoid the confusion that can arise from the many different names, in some cases from multiple languages, which are used to refer to a single species.

Latin was the language of scholars in the western world when Swedish biologist and physician Carl von Linne’, who often Latinized his own name as Carolus Linnaeus, developed the system for naming and classifying living species. As such, it makes historical sense that all formal names of species, and groups of species, are written as Latin or Greek, even if the words used are from a modern language. A very detailed set of rules, the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature governs how animal species are formally named so that no two animals are ever given the same binomial (two-part) name. A similar code governs non-animal species, so it is possible for a plant and an animal species to share the same scientific name. One rule common to all species is that the first part of the name shall be capitalized, but the second part is not. Both words are always written in italics to indicate the formal status of the name, thus what most people call cougar is known by biologists as Puma concolor.

Usually, the Latin used to name a species describes something about it. Back in 1771 Linnaeus himself first assigned a name to the cougar, calling it Felis concolor. Felis is Latin for “cat,” and concolor for “of uniform color.” Although more than one species can use the same genus (the first part of the name), as more cat species were discovered, the species was assigned a new genus, Puma, about 100 years after Linnaeus first described it. Modern biologists insist on grouping species by their genealogical relationships, many of which are still being deciphered. So it's not unusual for species to be reassigned to a different group, including genus, as new information becomes available. In either case, the specific epithet (the second name) usually remains the same.

New species are often discovered even within museum collections. Many of these are very similar to other species and may have been misidentified in the collection. If the species were new to scientists, they likely would have been described long ago, so the process of finding new species among existing collections has become more cumbersome over time. The species of frog my colleague and I described in 1996 belonged to a group of about 90 closely related species, so we had to study the published descriptions of all those species, and examine specimens of dozens of them, to determine if what we had was indeed an unnamed species. And with approximately 5,000 species, frogs are a relatively small group. For instance, more than 400,000 species of beetle have been formally described to date, and there are likely more unnamed species than there are biologists qualified to describe them.

Text and illustration by Daniel Meinhardt