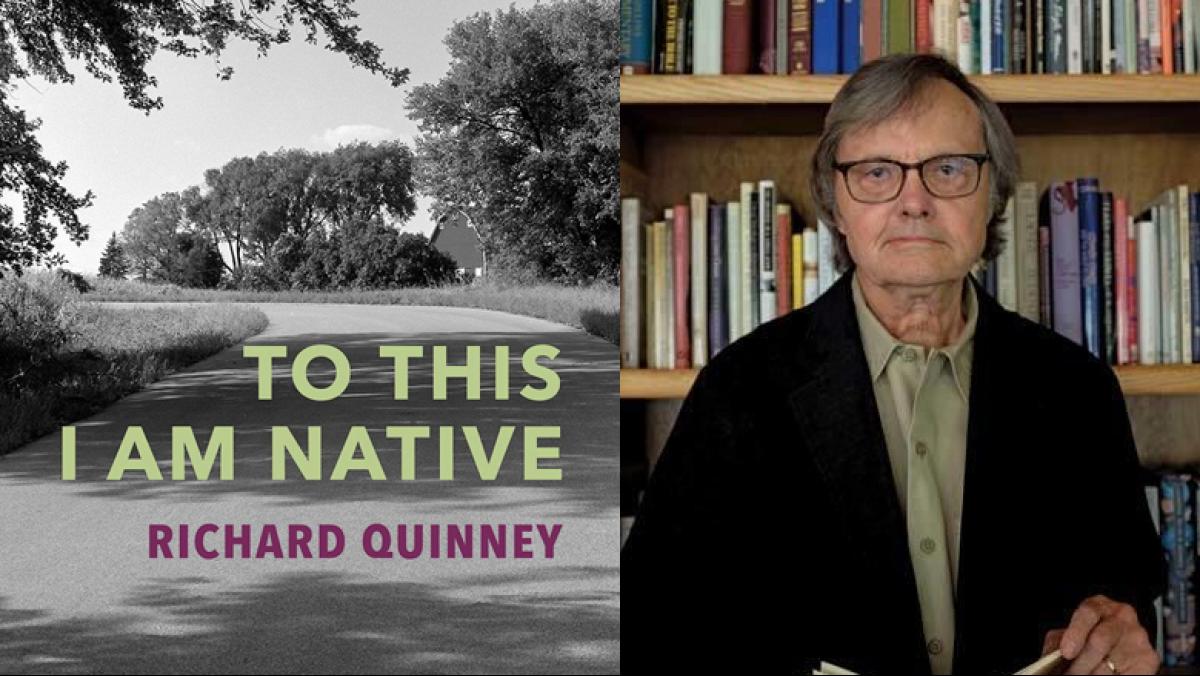

Readers of Wisconsin People & Ideas need no elaborate introduction to writer/photographer/philosopher Richard Quinney, whose “Elegy for a Family Farm” was featured in the Winter 2018 issue. What readers may not know is that Quinney’s Borderland Books, located in Madison, has for more than a decade offered an outlet for a variety of volumes on Wisconsin themes, naturally including his own combinations of photography and rumination. Borderland volumes, not large in number, are notable for their craftsmanship, right down to the careful choice of paper stock and binding. His new title, To This I Am Native, reflects the publisher’s continued determination to convey our sense of place here in Wisconsin through the aesthetic of an art book.

Most if not all of Quinney’s works draw from his farm-boy origins near Delavan, the history of the family farm going back several generations, and the reality of his own life as the last surviving family member and remaining steward of the land. But it is also important to note that his academic life as a prominent sociologist and founder of a field of study within criminology has shaped his way of writing about Wisconsin and even, perhaps, his use of the camera. He wishes to look closely and wants us, his readers, to look closely, too, at the landscape for its own sake, not merely as an extension of human need and desire.

In To This I Am Native the pictures do most of the talking, and the prose is spare. Quinney wants to tell us about his 2001 return to the farm, and how the return prompts a visual inventory of items left behind. The images that populate this volume reflect a certain starkness—no people are to be seen save the shadow of Quinney himself with his tripod, taking a picture—but also a naturalness of the landscape. He captures the fields and the buildings from many angles with a riveting intensity that, perhaps, only black and white photography can convey. Quinney looks carefully at the animal population, especially birds who make their homes on the farm. Winter adds a special sense of what could be taken as bleakness, but instead reflects the natural order of the season in which Quinney finds himself.

The interior of the house, seen through mundane objects such as an old Ellington piano, a vase on a counter with a nature scene above, or a dining room view of the yard, underscores a sense of transition. Quinney’s own lymphocytic leukemia, the author suggests, brings that transition into stark clarity: The farm is not timeless, neither is the artist-author recording its last moments under family guidance. But the farm has a presence, and he wants us to see that presence up close, accurately, as a Midwest moment.

Readers will treasure that candor as well as the artistry of this small volume. Perhaps, however, they will treasure more the ways in which it captures the creator of the volume, offering his own sometime rural Wisconsin life as a metaphor for our complicated, often conflicted, modern lives.